A good query letter makes a good impression, a bad query letter earns a swift rejection.

Just when you think you’re done writing the manuscript and take a sigh of relief, the wrecking ball of reality hits you with more to do. Now you must find takers for your book who’ll in turn, find you the buyers for it. Now, there’s more writing to do; a careful and precise piece that wins over the agent or the publishing house. That apart, there’s the all-essential editing, proofreading, typesetting… the works!

So there is a lot you have to do once you’re done writing the draft. Putting a book out there is no easy task. It becomes easy only once when you’re established in the market. JK Rowling and Jeffrey Archer sure don’t have to worry about writing query letters anymore.

If you’ve chosen the high road of self-publishing then you don’t have to sweat about all this at all. For others taking the traditional route, we’ve got a guide to help you write a dynamic query letter which is your best shot at getting a reputable literary agent’s attention.

Though there are no standard rules to do this, the following are some tips to help you compose a query letter that positions you as a talented and trustworthy author and your book as a valuable investment.

#1 Pay attention to the submission criteria

You must first decide if you want to approach an agent or a publisher. Before you start writing, spend some time to investigate the agent and make sure that they are likely to be interested. First look at their website and their submission guidelines. Be careful that you follow the instructions on their site.

You could also get a copy of the Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook, which lists the agents with their clients and informs you about how to approach them.

#2 Personalize the letter for each agent

Agents go through hundreds of such letters every month and can easily tell when it’s just a copy and paste job. It indicates that the author hasn’t done their research on the agent or the agency they’re querying.

Without personalization, your letter is just spam. One neat way to add a personal touch to your query is to reference*the agent’s existing clients.

“I am highly inspired by your client, Jacob Campen. The tense setting of Going Deep Down was a major influence on my novel.”

If something the agent has said or written comes up in your research, let it slide in. When it comes to making an impression, this trick does it!

“I read the interview you did with Humanoid Ink. Your views about lack of diversity in Sci-Fi really resonated with me. My book attempts to address this and bring a touch of pluralism to the genre.”

Don’t be too loud about it. Just make it a point to show that you’ve put in the efforts to pick the right agent.

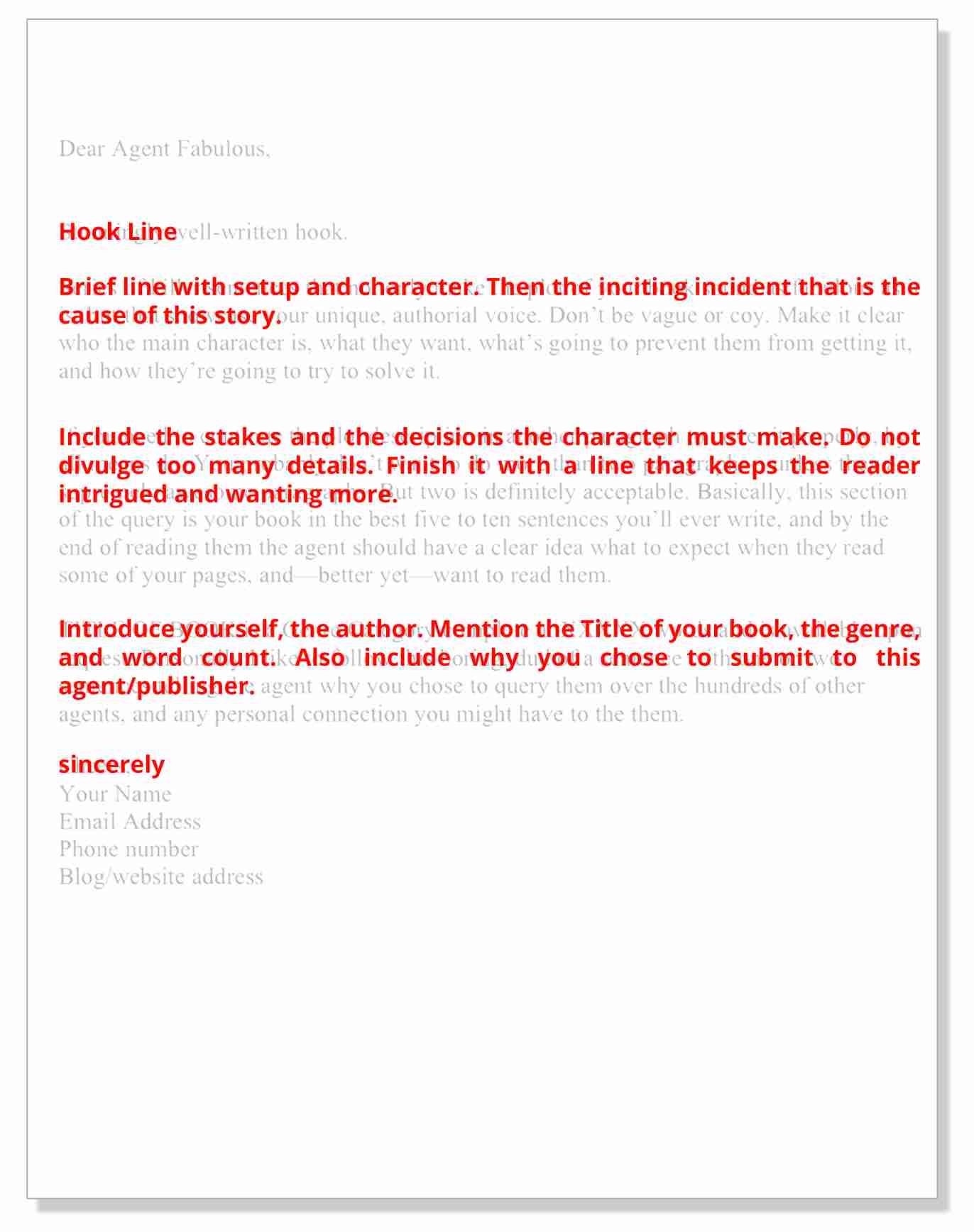

#3 Craft an irresistible hook

Most writers of popular fiction try to make the book un-put-downable for their readers in the first few pages. In a query letter, you have to do this with just a few lines. This part of the letter is known as “the hook.”

This can be done with anything that immediately captures the interest of the agent/producer: a quote, a controversial question or something that leaves the reader briefly stunned.

The purpose of the hook is to show agents how your book is positioned differently than thousands of others in your genre.

#4 Attach an Intriguing synopsis

If a synopsis is specified in the requirements, attach one to go with your letter. This is the tricky part where authors get confused with what to and what not to add. Don’t struggle with telling every significant event in the book. But don’t make it a dry laundry list of events either. Let it read like a condensed form of your story without giving away any main bits.

#5 Keep it short

Most amateurs end up writing too much to impress. Remember that the query letter serves as the basic intro to your book (title, word count, genre) along with a teaser thrown in.

Again, don’t divulge into the details of your story. Keep the letter short, say 300 to 400 words at the most and keep it concise, orderly, and organized.

A good query letter is brief and to the point, no more than one page long. One page designed to intrigue, not crammed from top to bottom with narrow margins.

#6 Language is important

Treat this as a Business Letter. Which means, it has to be crisp and powerful. Additionally, your flair for writing and what the book holds should reflect in the letter. The language which fills the text should be vivid, specific and dynamic.

The one-line description or “The Hook” can make or break the deal for you. Use all your imagination and the vocabulary you’ve gathered over time to create an arresting, unforgettable piece that shows the heart and soul of your novel.

Be honest about yourself. Don’t exaggerate your experience. Mention background only if it enhances your credibility for writing this book. If you have any published works in the bag, highlight such credentials to establish yourself as a sincere candidate. Be sure you’ve included the following details about your book:

- Title

- Word count

- Genre

- Audience Comp Titles

The next step is super crucial.

#7 Proofread the Letter Thoroughly

There is zero margin for error when you’re writing to an agent. If they read your work and find a typo in some sentence, or a sentence that makes no sense, they won’t read further. If you don’t put the time and effort into your book, neither will they.

Make sure you create a workmanlike business letter, so it does the job. It’s short, smooth-flowing, written in a persuasive, specific language, with no errors of any kind – no typos, misplaced punctuations, spelling or grammatical miscues whatsoever. Remember, letter-perfect!

#8 A note of thanks in the Last paragraph

Make the last one a small section which shows your gratitude to the agent for taking out the time to read your letter and considering your proposal. Don’t make it too flowery though, let it have a professional tone right till the end.

Get Your Query Letter Professionally Reviewed

PaperTrue is dedicated to helping authors chase their dreams. Like every written document, we also edit and proofread query letters with great panache. Our editors will edit your query to stress on the most fascinating aspects of your work, and also highlight any red flags that might prevent an agent from requesting your manuscript. We also improve your query’s lead paragraph and make your pitch more precise and efficient. With our expert editors to assist you, you’ll also learn how to write your next query letter more wisely.

Keep writing, be focused and stay professional. All the best!