No writer can reach their full potential without an editor that sharpens their words. A professional editor makes the difference between a bestseller and a flop, so you need to find the right person to work with. But how to find a book editor that is a perfect match for not only your manuscript but also you, the writer?

That’s precisely the question we’ll be answering.

Book editing is a long and layered process. So if you think you need to hire one person and be done with it, you’re in for a surprise! Professional editing for any book is handled by a team of book editors who perform different types of edits on your manuscript.

Unless you find a superhuman editor who can handle it all, you’ll have to decide what type of book editor you’re looking for. Most writers end up finding a team of book editors to work on their book, comprising four editors:

- Developmental editor

- Copy editor

- Line editor

- Proofreader

But let’s not stray from our question: how to find a book editor to work on your manuscript?

There are eight steps to finding the right book editor. Follow them well and you’ll have an editorial team that can refine your book to perfection!

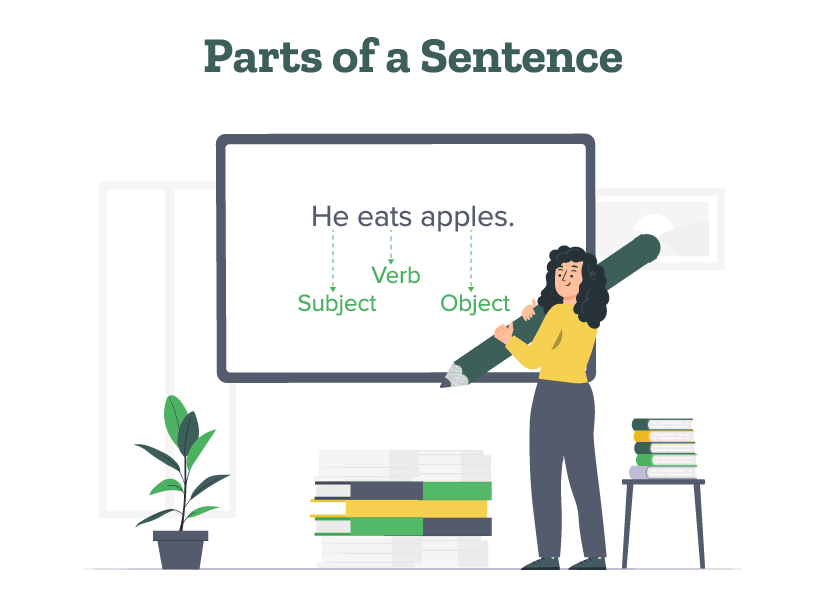

1. Understand the types of editing

There are four types of editing: developmental editing, line editing, copy editing, and proofreading. Let’s quickly understand them!

-

-

- Developmental editing: Developmental editors rectify any problems with structure, pacing, character development, plot, and themes. It is the first step of editing a book.

- Line editing: Line editors concentrate on paragraph and sentence-level corrections, improving clarity, flow, and writing style. They’ll help you tighten up your prose, get rid of any awkward phrasing, and make sure your voice shines through.

- Copy editing: Copy editors address grammar, punctuation, spelling, and consistency errors. They’ll also make sure you stick to the style guidelines for your genre or publishing house.

- Proofreading: This is the final step where the remaining errors in grammar, punctuation, spelling, capitalization, and formatting are corrected.

-

Now, you can determine your editing needs. If you’ve just finished your first draft and are unsure about the plot, structure, pacing, and characters, opt for developmental editing. However, if you’re confident about your story but unsure about the language used, choose line editing.

Alternatively, if your manuscript has a solid structure, engaging content, and polished writing style, skip developmental and line editing. In this case, you can proceed directly with copyediting and proofreading services.

2. Gather recommendations from personal and professional networks

Reach out to fellow writers, authors, and writing community members for editor recommendations. You can also research websites like Reedsy, Editorial Freelancers Association, Upwork, and Freelance Editors’ Network to find editors.

Plus, joining online writing forums, book review clubs, and social media groups is a fantastic way to get editor suggestions. The following is a list of online writing forums, book review clubs, and social media groups you can join:

-

-

-

-

- Writer’s Digest Forum

- Scribophile

- Goodreads

- Andrew Luck Book Club

- Reese’s Book Club

- The Oprah Winfrey Book Club

- The Write Life Community ( Facebook)

- Writers Helping Writers (Facebook)

-

-

-

Another insider tip? Attend writing conferences, workshops, and events to gather editor referrals. Also, don’t forget to ask your writing mentors, teachers, or any other industry gurus you know for editor recommendations.

The next step of how to find editors is optional. If you’ve not chosen a literary agent, you can skip this and directly see the next step of comparing services.

3. Consider referrals from literary agents

If you’re going the traditional publishing way, don’t be afraid to ask your literary agent for editor recommendations. Agents are pros at this stuff and usually have worked with several skilled editors before. They can easily find an editor who’s a perfect fit for your book.

It’s crucial to communicate with your agent throughout the process. Don’t just take their editor’s suggestions blindly. Make sure you’re constantly keeping them in the loop about your editing journey.

An important step of how to find a book editor is to compare the services provided by editing firms and freelancers. Let’s understand this step!

4. Compare editing services: firms vs. freelancers

When it comes to editing firms vs. freelancers, it’s all about finding your perfect match. This involves comparing the types of editing provided, turnaround times, the software they use, pricing, communication style, and personal rapport.

Also, review the editor’s or firm’s contract terms, including confidentiality, intellectual property rights, and termination clauses. With this, check if the editor or firm provides any additional services like book cover design, eBook conversion, book marketing, and distribution.

If you want to self-publish your book, check whether they provide self-publishing services like uploading it on self-publishing platforms.

Reviews are also your best guide to choosing the right book editing service. PaperTrue, for example, has a rating of 4.6/5 on Reviews.io and 4.8/5 on Google Reviews

Do your research and trust your instincts. Schedule a call or a meeting to decide if the editor is a perfect fit for your book.

5. Analyze their experience in your genre

Channel your inner Sherlock Holmes to uncover every detail of your editor’s professional history. Investigate their background and see if they’ve worked on books similar to yours. Have they edited anything in your niche before? Do they have a track record of success with stories like yours?

Check if they’re a part of online writing communities, groups, and book clubs related to your genre. Plus, ask for references for authors they’ve worked with before. Also, read their reviews and testimonials on their author’s website, social media platforms, and other online platforms.

If they organize workshops related to editing in your genre, this also demonstrates their passion for your genre.

The next step of how to find an editor for your book is equally crucial. Let’s explore this in detail!

6. Understand the costs involved

It’s crucial to have a clear understanding of the costs involved. While some editors charge by the word, others may charge by the hour or offer package rates. Here are estimated rates for a 50,000-word novel:

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Developmental editing: $0.03 to $0.08 per word

-

-

-

-

-

Estimated cost: $1,500 to $4,000

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Line editing: $0.02 to $0.06 per word

-

-

-

-

-

-

Estimated cost: $1,000 to $3,000

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Copyediting: $0.01 to $0.05 per word

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Estimated cost: $500 to $2,500

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Proofreading: $0.01 to $0.03 per word

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Estimated cost: $500 to $1,500

However, editing rates can vary significantly based on factors such as the editor’s experience, the level of editing required, and the manuscript’s complexity and length.

Request detailed quotes from multiple editors and carefully review what’s included in each package. Consider your budget and the value you place on the editing process.

A vital step of how to find an editor for a book is requesting a sample edit. Let’s quickly understand this step!

7. Request a sample edit

To get a firsthand sense of an editor’s style and approach, request a sample edit. For a sample edit, include manuscript sections that need improvement or areas where you struggle with clarity, pacing, or flow.

To test an editor, you can also add intentional errors in the sample you send and see if they can spot them. Some strategies you can use to test editors at this stage are:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Create a sample that incorporates multiple writing styles, such as descriptive prose, dialogue, and action scenes, all within the same excerpt. Ask the editor to analyze and provide feedback on each style separately

- Introduce subtle inconsistencies in character descriptions, motivations, or behaviors within your sample. Analyze if the editor can understand these inconsistencies.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Communicate your expectations for the sample edit, including the desired type of editing. Also, clarify the format in which you’ll be sending the sample (e.g., Microsoft Word, Google Docs, or PDF.) After this, set a deadline for receiving the sample edit.

Once you receive the sample edit, analyze the editor’s editing style, the depth of their feedback, and how well they enhance your unique voice.

Now let’s see the last step to finding a book editor!

8. Assess their communication and compatibility

You’ll be collaborating closely with your editor throughout the editing process. Hence, it’s essential to find someone who is responsive, professional, and easy to work with.

Pay attention to how promptly they reply to your inquiries, how clearly they communicate their services and expectations, and whether they take the time to understand your goals and concerns.

Now you can begin your journey of finding a professional editor. While you can still Google “How to find an editor for my book?”, rest assured that this guide can help you right up to publishing. For readers searching for “How to find an editor for your novel?”, the steps remain the same.

Checklist to find the perfect book editor

We’ve made a checklist of questions to help you find the right book editor. You can use these questions to narrow down your search or prepare your own checklist based on this model!

If you require high-quality book editing services, consider contacting PaperTrue. Our trained team provides all types of editing, eliminates errors, and offers in-depth feedback.

With this, we also offer additional services like creating a book cover design, audiobook, and copyright page, book printing, eBook conversion, formatting, book distribution, and marketing. We can also draft a query letter, book summary, blurb, and author profile for you.

What did you think about this article about how to find an editor for a book? Share your thoughts in the comments section!

Here are some useful resources for you: