- A List of Writing Contests in 2022 | Exciting Prizes!

- Em Dash vs. En Dash vs. Hyphen: When to Use Which

- Book Proofreading 101: The Beginner’s Guide

- Screenplay Editing: Importance, Cost, & Self-Editing Tips

- Screenplay Proofreading: Importance, Process, & Cost

- Script Proofreading: Rates, Process, & Proofreading Tips

- Manuscript Proofreading | Definition, Process & Standard Rates

- Tips to Write Better if English Is Your Second Language

- Novel Proofreading | Definition, Significance & Standard Rates

- Top 10 Must-Try Writing Prompt Generators in 2024

- 100+ Creative Writing Prompts for Masterful Storytelling

- Top 10 eBook Creator Tools in 2024: Free & Paid

- 50 Timeless and Unforgettable Book Covers of All Time

- What Is Flash Fiction? Definition, Examples & Types

- 80 Enchanting Christmas Writing Prompts for Your Next Story

- Your Guide to the Best eBook Readers in 2024

- Top 10 Book Review Clubs of 2025 to Share Literary Insights

- 2024’s Top 10 Self-Help Books for Better Living

- Writing Contests 2023: Cash Prizes, Free Entries, & More!

- Top 10 Book Marketing Services of 2024: Features and Costs

- What Is a Book Teaser and How to Write It: Tips and Examples

- Audiobook vs. EBook vs. Paperback in 2024: (Pros & Cons)

- How to Get a Literary Agent in 2024: The Complete Guide

- Alpha Readers: Where to Find Them and Alpha vs. Beta Readers

- Author Branding 101: How to Build a Powerful Author Brand

- A Guide on How to Write a Book Synopsis: Steps and Examples

- How to Write a Book Review (Meaning, Tips & Examples)

- 50 Best Literary Agents in the USA for Authors in 2024

- Building an Author Website: The Ultimate Guide with Examples

- Top 10 Book Printing Services for Authors in 2024

- 10 Best Free Online Grammar Checkers: Features and Ratings

- Top 10 Paraphrasing Tools for All (Free & Paid)

- Top 10 Book Editing Software in 2024 (Free & Paid)

- What Are Large Language Models and How They Work: Explained!

- Top 10 Hardcover Book Printing Services [Best of 2024]

- 2024’s Top 10 Setting Generators to Create Unique Settings

- Different Types of Characters in Stories That Steal the Show

- Top 10 Screenplay & Scriptwriting Software (Free & Paid)

- 10 Best AI Text Generators of 2024: Pros, Cons, and Prices

- Top 10 Must-Try Character Name Generators in 2024

- 10 Best AI Text Summarizers in 2024 (Free & Paid)

- 2024’s 10 Best Punctuation Checkers for Error-Free Text

- Top 10 AI Rewriters for Perfect Text in 2024 (Free & Paid)

- 11 Best Story Structures for Writers (+ Examples!)

- How to Write a Book with AI in 2024 (Free & Paid Tools)

- Writing Contests 2024: Cash Prizes & Free Entries!

- Patchwork Plagiarism: Definition, Types, & Examples

- 15 Powerful Writing Techniques for Authors in 2024

- Simple Resume Formats for Maximum Impact With Samples

- What Is a Complement in a Sentence? (Meaning, Types & Examples)

- What are Clauses? Definition, Meaning, Types, and Examples

- Persuasive Writing Guide: Techniques & Examples

- How to Paraphrase a Text (Examples + 10 Strategies!)

- 10 Best AI Writing Assistants of 2024 (Features + Pricing)

- Generative AI: Types, Impact, Advantages, Disadvantages

- A Simple Proofreading Checklist to Catch Every Mistake

- Top 10 AI Resume Checkers for Job Seekers (Free & Paid)

- 20 Best Comic Book Covers of All Time!

- How to Edit a Book: A Practical Guide with 7 Easy Steps

- How to Write an Autobiography (7 Amazing Strategies!)

- How to Publish a Comic Book: Nine Steps & Publishing Costs

- Passive and Active Voice (Meaning, Examples & Uses)

- How to Publish a Short Story & Best Publishing Platforms

- What Is Expository Writing? Types, Examples, & 10 Tips

- 10 Best Introduction Generators (Includes Free AI Tools!)

- Creative Writing: A Beginner’s Guide to Get Started

- How to Sell Books Online (Steps, Best Platforms & Tools)

- Top 10 Book Promotion Services for Authors (2025)

- 15 Different Types of Poems: Examples & Insight into Poetic Styles

- 25 Figures of Speech Simplified: Definitions and Examples

- 10 Best Book Writing Apps for Writers 2025: Free & Paid!

- Top 10 AI Humanizers of 2025 [Free & Paid Tools]

- Top 101 Bone-Chilling Horror Writing Prompts

- How to Write a Poem: Step-by-Step Guide to Writing Poetry

- Top 10 Book Writing Software, Websites, and Tools in 2025

- 100+ Amazing Short Story Ideas to Craft Unforgettable Stories

- The Top 10 Literary Devices: Definitions & Examples

- Top 10 AI Translators for High-Quality Translation in 2025

- Top 10 AI Tools for Research in 2025 (Fast & Efficient!)

- 50 Best Essay Prompts for College Students in 2025

- Top 10 Book Distribution Services for Authors in 2025

- Best 101 Greatest Fictional Characters of All Time

- Top 10 Book Title Generators of 2025

- Best Fonts and Sizes for Books: A Complete Guide

- What Is an Adjective? Definition, Usage & Examples

- How to Track Changes in Google Docs: A 7-Step Guide

- Best Book Review Sites of 2025: Top 10 Picks

- Parts of a Book: A Practical, Easy-to-Understand Guide

- What Is an Anthology? Meaning, Types, & Anthology Examples

- How to Write a Book Report | Steps, Examples & Free Template

- 10 Best Plot Generators for Engaging Storytelling in 2025

- 30 Powerful Poems About Life to Inspire and Uplift You

- What Is a Poem? Poetry Definition, Elements, & Examples

- Metonymy: Definition, Examples, and How to Use It In Writing

- 10 Best AI Detector Tools in 2025

- How to Write a CV with AI in 9 Steps (+ AI CV Builders)

- What Is an Adverb? Definition, Types, & Practical Examples

- How to Create the Perfect Book Trailer for Free

- Writing Contests 2025: Cash Prizes, Free Entries, and More!

- Top 10 Book Publishing Companies in 2025

- 14 Punctuation Marks: A Guide on How to Use with Examples!

- Translation Services: Top 10 Professional Translators (2025)

- What is a Book Copyright Page?

- Final Checklist: Is My Article Ready for Submitting to Journals?

- 8 Pre-Publishing Steps to Self-Publish Your Book

- 7 Essential Elements of a Book Cover Design

- How to Copyright Your Book in the US, UK, & India

- Beta Readers: Why You Should Know About Them in 2024

- How to Publish a Book in 2024: Essential Tips for Beginners

- ISBN Guide 2024: What Is an ISBN and How to Get an ISBN

- Book Cover Design Basics: Tips & Best Book Cover Ideas

- Why and How to Use an Author Pen Name: Guide for Authors

- How to Format a Book in 2025: 7 Tips for Book Formatting

- What is Manuscript Critique? Benefits, Process, & Cost

- How to Hire a Book Editor in 5 Practical Steps

- Self-Publishing Options for Writers

- How to Promote Your Book Using a Goodreads Author Page

- 7 Essential Elements of a Book Cover Design

- What Makes Typesetting a Pre-Publishing Essential for Every Author?

- 4 Online Publishing Platforms To Boost Your Readership

- Typesetting: An Introduction

- Quick Guide to Novel Editing (with a Self-Editing Checklist)

- 10 Best Self-Publishing Companies of 2024: Price & Royalties

- Self-Publishing vs. Traditional Publishing: 2024 Guide

- How to Publish a Book in 2024: Essential Tips for Beginners

- ISBN Guide 2024: What Is an ISBN and How to Get an ISBN

- How to Publish a Book on Amazon: 8 Easy Steps [2024 Update]

- What are Print-on-Demand Books? Cost and Process in 2024

- What Are the Standard Book Sizes for Publishing Your Book?

- Top 10 EBook Conversion Services for 2024’s Authors

- How to Market Your Book on Amazon to Maximize Sales in 2024

- Top 10 Hardcover Book Printing Services [Best of 2024]

- How to Find an Editor for Your Book in 8 Steps (+ Costs!)

- What Is Amazon Self-Publishing? Pros, Cons & Key Insights

- Manuscript Editing in 2024: Elevating Your Writing for Success

- Know Everything About How to Make an Audiobook

- A Simple 14-Point Self-Publishing Checklist for Authors

- How to Write an Engaging Author Bio: Tips and Examples

- Book Cover Design Basics: Tips & Best Book Cover Ideas

- How to Publish a Comic Book: Nine Steps & Publishing Costs

- Why and How to Use an Author Pen Name: Guide for Authors

- How to Sell Books Online (Steps, Best Platforms & Tools)

- A Simple Guide to Select the Best Self-Publishing Websites

- 10 Best Book Cover Design Services of 2025: Price & Ratings

- How Much Does It Cost to Self-Publish a Book in 2025?

- How to Self-Publish a Book: Tips and Prices (2025)

- Quick Guide to Book Editing [Complete Process & Standard Rates]

- How to Distinguish Between Genuine and Fake Literary Agents

- What is Self-Publishing? Everything You Need to Know

- How to Copyright a Book in 2025 (Costs + Free Template)

- How to start your own online publishing company?

- 8 Tips To Write Appealing Query Letters

- Self-Publishing vs. Traditional Publishing: 2024 Guide

- How to Publish a Book in 2024: Essential Tips for Beginners

- ISBN Guide 2024: What Is an ISBN and How to Get an ISBN

- What are Print-on-Demand Books? Cost and Process in 2024

- How to Write a Query Letter (Examples + Free Template)

- Third-person Point of View: Definition, Types, Examples

- How to Write an Engaging Author Bio: Tips and Examples

- How to Publish a Comic Book: Nine Steps & Publishing Costs

- Top 10 Book Publishing Companies in 2025

- How to Create Depth in Characters

- Starting Your Book With a Bang: Ways to Catch Readers’ Attention

- Research for Fiction Writers: A Complete Guide

- Short stories: Do’s and don’ts

- How to Write Dialogue: 7 Rules, 5 Tips & 65 Examples

- What Are Foil and Stock Characters? Easy Examples from Harry Potter

- How To Write Better Letters In Your Novel

- On Being Tense About Tense: What Verb Tense To Write Your Novel In

- How To Create A Stellar Plot Outline

- How to Punctuate Dialogue in Fiction

- On Being Tense about Tense: Present Tense Narratives in Novels

- The Essential Guide to Worldbuilding [from Book Editors]

- What Is Point of View? Definition, Types, & Examples in Writing

- How to Create Powerful Conflict in Your Story | Useful Examples

- How to Write a Book: A Step-by-Step Guide

- How to Write a Short Story in 6 Simple Steps

- How to Write a Novel: 8 Steps to Help You Start Writing

- What Is a Stock Character? 150 Examples from 5 Genres

- Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey: Worksheet & Examples

- Novel Outline: A Proven Blueprint [+ Free Template!]

- Character Development: 7-Step Guide for Writers

- What Is NaNoWriMo? Top 7 Tips to Ace the Writing Marathon

- What Is the Setting of a Story? Meaning + 7 Expert Tips

- Theme of a Story | Meaning, Common Themes & Examples

- What Is a Blurb? Meaning, Examples & 10 Expert Tips

- What Is Show, Don’t Tell? (Meaning, Examples & 6 Tips)

- How to Write a Book Summary: Example, Tips, & Bonus Section

- How to Write a Book Description (Examples + Free Template)

- 10 Best Free AI Resume Builders to Create the Perfect CV

- A Complete Guide on How to Use ChatGPT to Write a Resume

- 10 Best AI Writer Tools Every Writer Should Know About

- How to Write a Book Title (15 Expert Tips + Examples)

- 100 Novel and Book Ideas to Start Your Book Writing Journey

- Exploring Writing Styles: Meaning, Types, and Examples

- Mastering Professional Email Writing: Steps, Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Screenplay: Expert Tips, Steps, and Examples

- Business Proposal Guide: How to Write, Examples and Template

- Different Types of Resumes: Explained with Tips and Examples

- How to Create a Memorable Protagonist (7 Expert Tips)

- How to Write an Antagonist (Examples & 7 Expert Tips)

- Writing for the Web: 7 Expert Tips for Web Content Writing

- 10 Best AI Text Generators of 2024: Pros, Cons, and Prices

- What are the Parts of a Sentence? An Easy-to-Learn Guide

- How to Avoid AI Detection in 2024 (6 Proven Techniques!)

- How to Avoid Plagiarism in 2024 (10 Effective Strategies!)

- What Is Climax Of A Story & How To Craft A Gripping Climax

- What Is a Subject of a Sentence? Meaning, Examples & Types

- Object of a Sentence: Your Comprehensive Guide

- What Is First-Person Point of View? Tips & Practical Examples

- Second-person Point of View: What Is It and Examples

- 10 Best AI Essay Outline Generators of 2024

- Third-person Point of View: Definition, Types, Examples

- The Importance of Proofreading: A Comprehensive Overview

- Patchwork Plagiarism: Definition, Types, & Examples

- Simple Resume Formats for Maximum Impact With Samples

- The Ultimate Guide to Phrases In English – Types & Examples

- Modifiers: Definition, Meaning, Types, and Examples

- What are Clauses? Definition, Meaning, Types, and Examples

- Persuasive Writing Guide: Techniques & Examples

- What Is a Simile? Meaning, Examples & How to Use Similes

- Mastering Metaphors: Definition, Types, and Examples

- 10 Best AI Writing Assistants of 2024 (Features + Pricing)

- Generative AI: Types, Impact, Advantages, Disadvantages

- How to Publish a Comic Book: Nine Steps & Publishing Costs

- Essential Grammar Rules: Master Basic & Advanced Writing Skills

- Benefits of Using an AI Writing Generator for Editing

- Hyperbole in Writing: Definition and Examples

- 15 Best ATS-Friendly ChatGPT Prompts for Resumes in 2025

- How to Write a Novel in Past Tense? 3 Steps & Examples

- 10 Best Spell Checkers of 2025: Features, Accuracy & Ranking

- Foil Character: Definition, History, & Examples

- 5 Key Elements of a Short Story: Essential Tips for Writers

- How to Write a Children’s Book: An Easy Step-by-Step Guide

- How To Write a Murder Mystery Story

- What Is an Adjective? Definition, Usage & Examples

- Metonymy: Definition, Examples, and How to Use It In Writing

- Fourth-Person Point of View: A Unique Narrative Guide

- How to Write a CV with AI in 9 Steps (+ AI CV Builders)

- What Is an Adverb? Definition, Types, & Practical Examples

- How to Write A Legal Document in 6 Easy Steps

- 10 Best AI Story Generators in 2025: Write Captivating Tales

- How to Introduce a Character Effectively

- What is Rhetoric and How to Use It in Your Writing

- How to Write a Powerful Plot in 12 Steps

- How to Make Money as a Writer: Your First $1,000 Guide

- How to Write SEO Content: Tips for SEO-Optimized Content

- Types of Introductions and Examples

- How to Create Marketing Material

Still have questions? Leave a comment

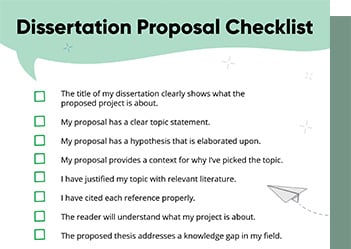

Checklist: Dissertation Proposal

Enter your email id to get the downloadable right in your inbox!

Examples: Edited Papers

Enter your email id to get the downloadable right in your inbox!

Need

Editing and

Proofreading Services?

How to Write a Poem: Step-by-Step Guide to Writing Poetry

Apr 08, 2025

Apr 08, 2025 6

min read

6

min read

Whether you’re writing poetry for a class or as a hobby, it can be difficult to get started. Precisely how do you write a poem, and how to write a good poem at that? Do poems have to rhyme? How to write a free verse poem? The questions are endless, but the process is more or less the same.

So, let’s unravel the art of poem-writing! We’ll tell you everything from how to start a poem to how to end one. But first, you’d probably want to go through our article on what a poem is, its elements, and its types. Now, let’s get started!

Understanding Poetry

Poetry is a unique form of creative writing that uses language in a condensed and powerful way to evoke emotions, convey ideas, and create a sense of connection with the reader. Unlike prose, poetry often relies on the musicality of words, the rhythm of stressed and unstressed syllables, and the strategic use of literary devices such as metaphor, simile, and imagery. These elements help to create a rich and layered meaning that can be interpreted in various ways.

Here’s how to write a poem:

- Read at least ten other poems

- List topics you feel passionate about

- Consider poetic form, but not too much

- Start writing, prioritizing sound

- Google synonyms, antonyms, and rhyming words

- Create original and striking imagery

- Use literary devices

- Choose an appropriate title

- Edit and proofread your poem

As you can see, this is a complete guide on how to write a poem for beginners. Let’s take an in-depth look.

1. Read at least ten other poems

All good poem writing comes from reading. If you want your poem to resonate with readers, you need to find out what resonates with you. Ideally, you should be a habitual reader of poetry. But if you’re writing a poem for class or tying it out as a hobby, try reading at least ten different types of poems.

Each form offers its own unique way to explore and express ideas. For instance, blank verse poetry follows a specific meter, often iambic pentameter, but does not rhyme, while free verse poetry is unrestricted by conventional rules such as rhyme schemes and meter.

All good poem writing comes from reading. If you want your poem to resonate with readers, you need to find out what resonates with you. Ideally, you should be a habitual reader of poetry. But if you’re writing a poem for class or tying it out as a hobby, try reading at least ten different types of poems.

Each form offers its own unique way to explore and express ideas. For instance, blank verse poetry follows a specific meter, often iambic pentameter, but does not rhyme, while free verse poetry is unrestricted by conventional rules such as rhyme schemes and meter.

Here are some poems you should read as a beginner:

- The Sun Rising by John Donne (Metaphysical poem)

- In Kyoto… by Matsuo Basho (Haiku)

- Sonnet 18 by William Shakespeare (Sonnet)

- I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud by William Wordsworth (Pastoral lyric)

- Because I could not stop for Death by Emily Dickinson (Lyrical poem)

- The Road Not Taken by Robert Frost (Narrative poem)

- Jabberwocky by Lewis Carroll (Nonsense poem)

- Howl by Allen Ginsberg (Free verse, “Beat epic”)

- Tonight by Agha Shahid Ali (Ghazal)

- Concrete Cat by Dorthi Charles (Concrete poetry)

Likely, you won’t understand many of these poems on the first read; most readers don’t. Read them three or four times, and once you get the gist, look up their explanations. That’ll clear things up and show you the possibilities in every type of poetry.

Poetry is not just about following rules; it’s about breaking them to create something new and meaningful, whether you choose to adhere to the same meter throughout or experiment with different rhythms.

2. List topics you feel passionate about

Do you want to know how to write good poetry? Know what you’re writing about. Your poem will ring hollow if you write from a shallow state of mind.

“Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.” —William Wordsworth

Now, emotion is quite important in poetry, but your poem doesn’t always have to come from an emotional place. You should, however, care deeply about your topic. You can write a good poem only if the topic matters to you.

Here’s how you can narrow down some topics:

- Reflect on your life experiences, friendship, family, romance, joy, and heartbreak.

- Think about philosophy: What are your big existential questions?

- Observe plants, animals, and natural phenomena, and document how they make you feel.

- Ponder upon the social issues around you.

- Try freewriting and journaling.

- If you want to challenge yourself, use poetry writing prompts.

3. Consider poetic form, but not too much

The type of poem you write can affect your poem-writing process. A haiku, for example, dwells on stark images, whereas a limerick is likely to be funny. If you really want to try your hand at a concrete poem, your theme, word choice, and tone will change accordingly. Plus, some forms like sonnets or ghazals are inherently trickier than a haiku or free verse.

So, you should consider the poetic form you’d be most comfortable with. Understanding different rhyme schemes can also help you decide how to structure your written poetry. Make sure not to get caught up in the rules, though. Everyone’s creative process is different. Some poets thrive under the limits of form, while others prefer the freedom of composition. Find what works for you and practice it a few times.

4. Start writing, prioritizing sound

Sound is incredibly important in a poem: It’s responsible for rhythm, which makes poetry pleasing to read. So when you begin to write, pay attention to how your words sound together. Try to create rhyming words, consonance, and assonance as you write. Pay attention to how your lines rhyme, as this can significantly impact the rhythm and flow of your poem. If you’re unsure about this, watch some poetry recitations online and compare them to written poems. This will help you “hear” the words as you write them down.

Consonance:

“Nary a grin grinned Rudolph Reed” —The Ballad of Rudolph Reed by Gwendolyn Brooks

Assonance:

“The lady is a sight

a might

a light” —Le sporting-club de Monte Carlo by James Baldwin

You’re probably wondering how to start a poem when you’ve never done it before. It’s simple, really: Just start! No one’s first attempt is Nobel-worthy, but that’s not the point. Simply focus on getting your words out as creatively as you can. If you happen to use a startling image or a tender metaphor while you’re at it, all the better!

It’s best to use pen and paper on your first try. It’s not only easier to organize your thoughts and cancel out lines, but also quicker. Plus, physical activity can help you focus better.

Does poetry have to rhyme?

No, poetry does not have to rhyme. Many poems achieve a musical effect through assonance alone while many others don’t have a musical effect at all. It all depends on your taste and preference while writing poems!

5. Google synonyms, antonyms, and rhyming words for a rhyme scheme

As beginners, it’s difficult to find the right words for your poem. So it’s perfectly fine to use Google or other tools to look for rhyming words, synonyms, or homophones. Even seasoned poets sometimes have to Google synonyms while writing poems!

Make sure you’re not asking an AI to produce a poem for you, though. That would defeat the purpose of the exercise! (Not to mention, AI-written poems lack originality, nuance, and soul.) But AI tools can be extremely useful while hunting for that slippery word that’s just the right fit in your line.

6. Create original and striking imagery

Imagery is the art of painting a picture using words, and you’re likely to do this in your poem without even realizing it. So pay attention to the images you create and make sure they’re not typical. This is quite important when learning how to write poetry for beginners. Images like a rose, the moon, and the nightingale are so overdone in poetry that they can cheapen your poem.

Depending on the tone and theme of your poem, imagery can even be jarring and disturbing. Here’s an example of how to write such a poem:

“What a thrill –

My thumb instead of an onion.

The top quite gone

Except for a sort of hinge

Of skin,

A flap like a hat,

Dead white.

Then that red plush.” —Cut by Sylvia Plath

Observe how Plath creates the original and raw image of the cut thumb. She uses metaphor (hinge of skin), simile (a flap like a hat), and color (dead white, red plush). You can also describe the senses of sound, smell, taste, and touch to create unique images.

So, make sure that the images you use are vivid and striking. Also, check whether they’re appropriate for your poem: Your images shouldn’t stick out for the wrong reason!

7. Use literary devices

Remember consonance and assonance? Those are literary devices or tools that make your writing more interesting to read. There are more of these, and you should use them in your poem:

Simile: Comparing dissimilar objects using “as” or “like”.

“O my Luve is like a red, red rose” —A Red, Red Rose by Robert Burns

Metaphor: Comparing two objects by saying that one thing is another.

“‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers -” —“Hope” is the thing with feathers by Emily Dickinson

Personification: Giving human characteristics to non-human entities.

“The fog comes

on little cat feet.” —Fog by Carl Sandburg

Symbolism: Using symbols to depict ideas or qualities.

The raven in Edgar Allen Poe’s poem The Raven symbolizes the narrator’s descent into madness.

Oxymoron: Placing contradictory terms together.

“Parting is such sweet sorrow.” —Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

Hyperbole: An exaggerated statement.

“Belinda smiled, and all the world was gay.” —The Rape of the Lock by Alexander Pope

Repetition: Repeating a word or phrase for impact.

“Break, break, break,

On thy cold gray stones, O Sea!” —Break, Break, Break by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Juxtaposition: Placing two things together for a direct comparison.

“Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.” —Fire and Ice by Robert Frost

Of all the tips on how to write a poem, this can be the toughest for beginners. In the beginning, using these poetic devices may come off as crafty or put-upon, but you’ll get better at it with practice. When in doubt, think of proverbs and adages: You’ll find the best figures of speech used naturally!

8. Choose an appropriate title

A poem deserves a fitting title; it’s sort of a crowning moment while writing poetry! If you’ve got a strong first line in your poem, you can just use that as the title. Another method is to use the central image, symbol, or theme of your poem as the title. You can even use an interesting line connected to your poem, so your title starts the poem before your first line does.

Whatever route you choose, the title of your poem should be impactful and fitting for the poem. Here are some great examples:

- Night Sky With Exit Wounds by Ocean Vuong

- Wild nights – Wild nights! By Emily Dickinson

- The Language of Dust by Asotto Saint

- A Small Needful Fact by Ross Gay

- [Didn’t Sappho say her guts clutched up like this?] by Marylyn Hacker

9. Edit and proofread your poem

The biggest rule of editing any document is to leave it alone for at least a week. This way, you can come back to your poem with a fresh, (slightly more) objective perspective. If you spend this time reading, you’ll have many examples of how to use literary devices in a poem. Enriched with this new knowledge, you can examine your poem and improve it further.

Here’s a poetry editing checklist for your poem:

- Read your poem aloud. Can you improve its rhythm and sound?

- If you’ve followed a meter, count the syllables and check the stress pattern.

- Check line breaks and stanzas to see if the poem can be more impactful if it’s structured differently.

- Examine your word choice and try out variations and synonyms where you’re unsure.

- Check your images: Are they vivid? Are they appropriate?

- Ensure you aren’t using any cliches.

- Check if the third and fourth lines of your quatrains rhyme, as this can enhance the poem’s rhythm and coherence.

- Remove all spelling, punctuation, and grammar errors.

The last step can be tricky for new poets since you have to balance poetic license with readability. This is precisely where poetry editing services can step in, helping you refine your poem with expert advice. If you can’t hire an editor, seek feedback on your poem from family, friends, or teachers.

That’s about everything you need to know about how to write a poem! Now, start reading poems so you can start writing one. You can begin brainstorming and listing down all ideas for poem writing. If you’d like some more writing tips, here are some resources that can help:

Frequently Asked Questions