- A List of Writing Contests in 2022 | Exciting Prizes!

- Em Dash vs. En Dash vs. Hyphen: When to Use Which

- Book Proofreading 101: The Beginner’s Guide

- Screenplay Editing: Importance, Cost, & Self-Editing Tips

- Screenplay Proofreading: Importance, Process, & Cost

- Script Proofreading: Rates, Process, & Proofreading Tips

- Manuscript Proofreading | Definition, Process & Standard Rates

- Tips to Write Better if English Is Your Second Language

- Novel Proofreading | Definition, Significance & Standard Rates

- Top 10 Must-Try Writing Prompt Generators in 2024

- 100+ Creative Writing Prompts for Masterful Storytelling

- Top 10 eBook Creator Tools in 2024: Free & Paid

- 50 Timeless and Unforgettable Book Covers of All Time

- What Is Flash Fiction? Definition, Examples & Types

- 80 Enchanting Christmas Writing Prompts for Your Next Story

- Top 10 Book Review Clubs of 2025 to Share Literary Insights

- 2024’s Top 10 Self-Help Books for Better Living

- Writing Contests 2023: Cash Prizes, Free Entries, & More!

- What Is a Book Teaser and How to Write It: Tips and Examples

- Audiobook vs. EBook vs. Paperback in 2024: (Pros & Cons)

- How to Get a Literary Agent in 2024: The Complete Guide

- Alpha Readers: Where to Find Them and Alpha vs. Beta Readers

- Author Branding 101: How to Build a Powerful Author Brand

- A Guide on How to Write a Book Synopsis: Steps and Examples

- How to Write a Book Review (Meaning, Tips & Examples)

- 50 Best Literary Agents in the USA for Authors in 2024

- Building an Author Website: The Ultimate Guide with Examples

- Top 10 Paraphrasing Tools for All (Free & Paid)

- Top 10 Book Editing Software in 2024 (Free & Paid)

- What Are Large Language Models and How They Work: Explained!

- Top 10 Hardcover Book Printing Services [Best of 2024]

- 2024’s Top 10 Setting Generators to Create Unique Settings

- Different Types of Characters in Stories That Steal the Show

- Top 10 Screenplay & Scriptwriting Software (Free & Paid)

- 10 Best AI Text Generators of 2024: Pros, Cons, and Prices

- Top 10 Must-Try Character Name Generators in 2024

- 10 Best AI Text Summarizers in 2024 (Free & Paid)

- 11 Best Story Structures for Writers (+ Examples!)

- How to Write a Book with AI in 2024 (Free & Paid Tools)

- Writing Contests 2024: Cash Prizes & Free Entries!

- Patchwork Plagiarism: Definition, Types, & Examples

- Simple Resume Formats for Maximum Impact With Samples

- What Is a Complement in a Sentence? (Meaning, Types & Examples)

- What are Clauses? Definition, Meaning, Types, and Examples

- Persuasive Writing Guide: Techniques & Examples

- How to Paraphrase a Text (Examples + 10 Strategies!)

- A Simple Proofreading Checklist to Catch Every Mistake

- Top 10 AI Resume Checkers for Job Seekers (Free & Paid)

- 20 Best Comic Book Covers of All Time!

- How to Edit a Book: A Practical Guide with 7 Easy Steps

- How to Write an Autobiography (7 Amazing Strategies!)

- How to Publish a Comic Book: Nine Steps & Publishing Costs

- Passive and Active Voice (Meaning, Examples & Uses)

- How to Publish a Short Story & Best Publishing Platforms

- What Is Expository Writing? Types, Examples, & 10 Tips

- 10 Best Introduction Generators (Includes Free AI Tools!)

- Creative Writing: A Beginner’s Guide to Get Started

- How to Sell Books Online (Steps, Best Platforms & Tools)

- Top 10 Book Promotion Services for Authors (2025)

- 15 Different Types of Poems: Examples & Insight into Poetic Styles

- 10 Best Book Writing Apps for Writers 2025: Free & Paid!

- Top 10 AI Humanizers of 2025 [Free & Paid Tools]

- How to Write a Poem: Step-by-Step Guide to Writing Poetry

- 100+ Amazing Short Story Ideas to Craft Unforgettable Stories

- The Top 10 Literary Devices: Definitions & Examples

- Top 10 AI Translators for High-Quality Translation in 2025

- Top 10 AI Tools for Research in 2025 (Fast & Efficient!)

- 50 Best Essay Prompts for College Students in 2025

- Top 10 Book Distribution Services for Authors in 2025

- Top 10 Book Title Generators of 2025

- Best Fonts and Sizes for Books: A Complete Guide

- What Is an Adjective? Definition, Usage & Examples

- How to Track Changes in Google Docs: A 7-Step Guide

- Best Book Review Sites of 2025: Top 10 Picks

- Parts of a Book: A Practical, Easy-to-Understand Guide

- What Is an Anthology? Meaning, Types, & Anthology Examples

- How to Write a Book Report | Steps, Examples & Free Template

- 10 Best Plot Generators for Engaging Storytelling in 2025

- 30 Powerful Poems About Life to Inspire and Uplift You

- What Is a Poem? Poetry Definition, Elements, & Examples

- Metonymy: Definition, Examples, and How to Use It In Writing

- How to Write a CV with AI in 9 Steps (+ AI CV Builders)

- What Is an Adverb? Definition, Types, & Practical Examples

- How to Create the Perfect Book Trailer for Free

- Top 10 Book Publishing Companies in 2025

- 14 Punctuation Marks: A Guide on How to Use with Examples!

- Translation Services: Top 10 Professional Translators (2025)

- 10 Best Free Online Grammar Checkers: Features and Ratings

- 30 Popular Children’s Books Teachers Recommend in 2025

- 10 Best Photobook Makers of 2025 We Tested This Year

- Top 10 Book Marketing Services of 2025: Features and Costs

- Top 10 Book Printing Services for Authors in 2025

- 10 Best AI Detector Tools in 2025

- Audiobook Marketing Guide: Best Strategies, Tools & Ideas

- 10 Best AI Writing Assistants of 2025 (Features + Pricing)

- How to Write a Book Press Release that Grabs Attention

- 15 Powerful Writing Techniques for Authors in 2025

- Generative AI: Types, Impact, Advantages, Disadvantages

- Top 101 Bone-Chilling Horror Writing Prompts

- 25 Figures of Speech Simplified: Definitions and Examples

- Best EBook Cover Design Services of 2025 for Authors

- Writing Contests 2025: Cash Prizes, Free Entries, and More!

- National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo)

- Best Horror Books of All Time (Must-Read List)

- Best Book Trailer Services

- Your Guide to the Best eBook Readers in 2026

- 10 Best Punctuation Checkers for Error-Free Text (2026)

- Master Circumlocution: Definition, Examples & Literary Uses

- Best Historical Fiction Books: 30 Must-Read Novels

- Best 101 Greatest Fictional Characters of All Time

- Writing Contests 2026: Free Entries and Cash Prizes!

- Top 10 Book Writing Software, Websites, and Tools in 2026

- Top 10 AI Rewriters for Perfect Text in 2026 (Free & Paid)

- What is a Book Copyright Page?

- Final Checklist: Is My Article Ready for Submitting to Journals?

- 8 Pre-Publishing Steps to Self-Publish Your Book

- 7 Essential Elements of a Book Cover Design

- How to Copyright Your Book in the US, UK, & India

- Beta Readers: Why You Should Know About Them in 2024

- How to Publish a Book in 2024: Essential Tips for Beginners

- Book Cover Design Basics: Tips & Best Book Cover Ideas

- Why and How to Use an Author Pen Name: Guide for Authors

- How to Format a Book in 2025: 7 Tips for Book Formatting

- What is Manuscript Critique? Benefits, Process, & Cost

- 10 Best Ghostwriting Services for Authors in 2025

- Best Manuscript Editing Services of 2025

- Best Manuscript Critique Services (2026): Top 10 Picks

- How To Format a Book in Google Docs (Step-by-Step)

- ISBN Guide: What Is an ISBN and How to Get an ISBN

- How to Hire a Book Editor in 5 Practical Steps

- Self-Publishing Options for Writers

- How to Promote Your Book Using a Goodreads Author Page

- 7 Essential Elements of a Book Cover Design

- What Makes Typesetting a Pre-Publishing Essential for Every Author?

- 4 Online Publishing Platforms To Boost Your Readership

- Typesetting: An Introduction

- Quick Guide to Novel Editing (with a Self-Editing Checklist)

- Self-Publishing vs. Traditional Publishing: 2024 Guide

- How to Publish a Book in 2024: Essential Tips for Beginners

- How to Publish a Book on Amazon: 8 Easy Steps [2024 Update]

- What are Print-on-Demand Books? Cost and Process in 2024

- What Are the Standard Book Sizes for Publishing Your Book?

- How to Market Your Book on Amazon to Maximize Sales in 2024

- Top 10 Hardcover Book Printing Services [Best of 2024]

- How to Find an Editor for Your Book in 8 Steps (+ Costs!)

- What Is Amazon Self-Publishing? Pros, Cons & Key Insights

- Manuscript Editing in 2024: Elevating Your Writing for Success

- Know Everything About How to Make an Audiobook

- A Simple 14-Point Self-Publishing Checklist for Authors

- How to Write an Engaging Author Bio: Tips and Examples

- Book Cover Design Basics: Tips & Best Book Cover Ideas

- How to Publish a Comic Book: Nine Steps & Publishing Costs

- Why and How to Use an Author Pen Name: Guide for Authors

- How to Sell Books Online (Steps, Best Platforms & Tools)

- A Simple Guide to Select the Best Self-Publishing Websites

- 10 Best Book Cover Design Services of 2025: Price & Ratings

- How Much Does It Cost to Self-Publish a Book in 2025?

- Quick Guide to Book Editing [Complete Process & Standard Rates]

- How to Distinguish Between Genuine and Fake Literary Agents

- What is Self-Publishing? Everything You Need to Know

- How to Copyright a Book in 2025 (Costs + Free Template)

- The Best eBook Conversion Services of 2025: Top 10 Picks

- 10 Best Self-Publishing Companies of 2025: Price & Royalties

- 10 Best Photobook Makers of 2025 We Tested This Year

- Book Cover Types: Formats, Bindings & Styles

- A Beginner’s Guide on How to Self Publish a Book (2025)

- Index in a Book: Definition, Purpose, and How to Use It

- How to Publish a Novel: Easy Step-By-Step Guide

- How to Design a Book Cover: From Concept to Covers That Sell

- ISBN Guide: What Is an ISBN and How to Get an ISBN

- 8 Tips To Write Appealing Query Letters

- Self-Publishing vs. Traditional Publishing: 2024 Guide

- How to Publish a Book in 2024: Essential Tips for Beginners

- What are Print-on-Demand Books? Cost and Process in 2024

- How to Write a Query Letter (Examples + Free Template)

- Third-person Point of View: Definition, Types, Examples

- How to Write an Engaging Author Bio: Tips and Examples

- How to Publish a Comic Book: Nine Steps & Publishing Costs

- Top 10 Book Publishing Companies in 2025

- 10 Best Photobook Makers of 2025 We Tested This Year

- Book Cover Types: Formats, Bindings & Styles

- Index in a Book: Definition, Purpose, and How to Use It

- How to Publish a Novel: Easy Step-By-Step Guide

- How to start your own online publishing company?

- How to Design a Book Cover: From Concept to Covers That Sell

- ISBN Guide: What Is an ISBN and How to Get an ISBN

- How to Create Depth in Characters

- Starting Your Book With a Bang: Ways to Catch Readers’ Attention

- Research for Fiction Writers: A Complete Guide

- Short stories: Do’s and don’ts

- How to Write Dialogue: 7 Rules, 5 Tips & 65 Examples

- What Are Foil and Stock Characters? Easy Examples from Harry Potter

- How To Write Better Letters In Your Novel

- On Being Tense About Tense: What Verb Tense To Write Your Novel In

- How To Create A Stellar Plot Outline

- How to Punctuate Dialogue in Fiction

- On Being Tense about Tense: Present Tense Narratives in Novels

- The Essential Guide to Worldbuilding [from Book Editors]

- What Is Point of View? Definition, Types, & Examples in Writing

- How to Create Powerful Conflict in Your Story | Useful Examples

- How to Write a Book: A Step-by-Step Guide

- How to Write a Short Story in 6 Simple Steps

- How to Write a Novel: 8 Steps to Help You Start Writing

- What Is a Stock Character? 150 Examples from 5 Genres

- Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey: Worksheet & Examples

- Novel Outline: A Proven Blueprint [+ Free Template!]

- Character Development: 7-Step Guide for Writers

- What Is NaNoWriMo? Top 7 Tips to Ace the Writing Marathon

- What Is the Setting of a Story? Meaning + 7 Expert Tips

- What Is a Blurb? Meaning, Examples & 10 Expert Tips

- What Is Show, Don’t Tell? (Meaning, Examples & 6 Tips)

- How to Write a Book Summary: Example, Tips, & Bonus Section

- How to Write a Book Description (Examples + Free Template)

- 10 Best Free AI Resume Builders to Create the Perfect CV

- A Complete Guide on How to Use ChatGPT to Write a Resume

- 10 Best AI Writer Tools Every Writer Should Know About

- How to Write a Book Title (15 Expert Tips + Examples)

- 100 Novel and Book Ideas to Start Your Book Writing Journey

- Exploring Writing Styles: Meaning, Types, and Examples

- Mastering Professional Email Writing: Steps, Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Screenplay: Expert Tips, Steps, and Examples

- Business Proposal Guide: How to Write, Examples and Template

- Different Types of Resumes: Explained with Tips and Examples

- How to Create a Memorable Protagonist (7 Expert Tips)

- How to Write an Antagonist (Examples & 7 Expert Tips)

- Writing for the Web: 7 Expert Tips for Web Content Writing

- 10 Best AI Text Generators of 2024: Pros, Cons, and Prices

- What are the Parts of a Sentence? An Easy-to-Learn Guide

- What Is Climax Of A Story & How To Craft A Gripping Climax

- What Is a Subject of a Sentence? Meaning, Examples & Types

- Object of a Sentence: Your Comprehensive Guide

- What Is First-Person Point of View? Tips & Practical Examples

- Second-person Point of View: What Is It and Examples

- 10 Best AI Essay Outline Generators of 2024

- Third-person Point of View: Definition, Types, Examples

- The Importance of Proofreading: A Comprehensive Overview

- Patchwork Plagiarism: Definition, Types, & Examples

- Simple Resume Formats for Maximum Impact With Samples

- The Ultimate Guide to Phrases In English – Types & Examples

- Modifiers: Definition, Meaning, Types, and Examples

- What are Clauses? Definition, Meaning, Types, and Examples

- Persuasive Writing Guide: Techniques & Examples

- What Is a Simile? Meaning, Examples & How to Use Similes

- Mastering Metaphors: Definition, Types, and Examples

- How to Publish a Comic Book: Nine Steps & Publishing Costs

- Essential Grammar Rules: Master Basic & Advanced Writing Skills

- Benefits of Using an AI Writing Generator for Editing

- Hyperbole in Writing: Definition and Examples

- 15 Best ATS-Friendly ChatGPT Prompts for Resumes in 2025

- How to Write a Novel in Past Tense? 3 Steps & Examples

- 10 Best Spell Checkers of 2025: Features, Accuracy & Ranking

- Foil Character: Definition, History, & Examples

- 5 Key Elements of a Short Story: Essential Tips for Writers

- How to Write a Children’s Book: An Easy Step-by-Step Guide

- How To Write a Murder Mystery Story

- What Is an Adjective? Definition, Usage & Examples

- Metonymy: Definition, Examples, and How to Use It In Writing

- Fourth-Person Point of View: A Unique Narrative Guide

- How to Write a CV with AI in 9 Steps (+ AI CV Builders)

- What Is an Adverb? Definition, Types, & Practical Examples

- How to Write A Legal Document in 6 Easy Steps

- 10 Best AI Story Generators in 2025: Write Captivating Tales

- How to Introduce a Character Effectively

- What is Rhetoric and How to Use It in Your Writing

- How to Write a Powerful Plot in 12 Steps

- How to Make Money as a Writer: Your First $1,000 Guide

- How to Write SEO Content: Tips for SEO-Optimized Content

- Types of Introductions and Examples

- What is a Cliffhanger? Definition, Examples, & Writing Tips

- How to Write Cliffhangers that Keep Readers Hooked!

- How to Write a Romance Novel: Step-by-Step Guide

- Top 10 Writing Tips from Famous Authors

- 10 Best Ghostwriting Services for Authors in 2025

- What is Ghostwriting? Meaning and Examples

- How to Become a Ghostwriter: Complete Career Guide

- How to Write a Speech that Inspires (With Examples)

- Theme of a Story | Meaning, Common Themes & Examples

- 10 Best AI Writing Assistants of 2025 (Features + Pricing)

- Generative AI: Types, Impact, Advantages, Disadvantages

- Worldbuilding Questions and Templates (Free)

- How to Avoid Plagiarism in 2025 (10 Effective Strategies!)

- How to Create Marketing Material

- What Is Worldbuilding? Steps, Tips, and Examples

- What is Syntax in Writing: Definition and Examples

- What is a Subplot? Meaning, Examples & Types

- Writing Challenges Every Writer Should Take

- What Is a Memoir? Definition, Examples, and Tips

- What Is Fiction? Definition, Types & Examples

- What Is Science Fiction? Meaning, Examples, and Types

- 50 Character Stereotypes: The Ultimate List!

- 50 Novel Writing Prompts (Categorized by Genre)

- 50 Haiku Writing Prompts For Your Inner Poet

- Direct Characterization: Definition, Examples & Comparison

- Indirect Characterization: Meaning, Examples & Writing Tips

- Direct vs Indirect Characterization: What’s the Difference

- How to Write Epic Fantasy

- 50 Non-fiction Writing Prompts For Your Inner Writer

- Master Circumlocution: Definition, Examples & Literary Uses

- How to Write a Good Villain (With Examples)

- How to Avoid AI Detection in 2026 (6 Proven Techniques!)

- How to Write a Cookbook: Step-by-Step Guide

Still have questions? Leave a comment

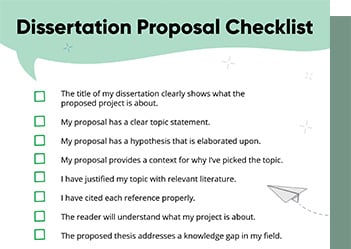

Checklist: Dissertation Proposal

Enter your email id to get the downloadable right in your inbox!

[contact-form-7 id="12425" title="Checklist: Dissertation Proposal"]

Examples: Edited Papers

Enter your email id to get the downloadable right in your inbox!

[contact-form-7 id="12426" title="Examples: Edited Papers"]Need

Editing and

Proofreading Services?

50 Character Stereotypes: The Ultimate List!

Jan 06, 2026

Jan 06, 2026 10

min read

10

min read

- Tags: Character, Types of Characters, Writers

Ever noticed how some characters feel instantly familiar? You meet them, and within minutes you know what they’re about. That’s not lazy writing, it’s the power of character stereotypes.

Character stereotypes are recognizable personality patterns that appear across storytelling formats, from novels and manga to films, TV shows, and even advertisements. They act as storytelling shortcuts, helping audiences quickly understand a character’s role, motivation, or conflict.

In this article, we’ll explore 50 popular character stereotypes, explain what makes each one tick, and give examples you’ll instantly recognize.

Make Your Characters Come To Life With Self-Publishing Now! Get Started

What are character stereotypes?

Character stereotypes are simplified and widely recognized character types built around specific traits, behaviors, or roles. They often reflect cultural expectations, storytelling traditions, or audience psychology.

They aren’t inherently bad. In fact, they:

- Make stories easier to understand

- Help readers connect quickly

- Create strong emotional responses

- Provide a base for character development

The problem only arises when stereotypes are used without depth, growth, or variation.

50 Common Character Stereotypes

1. The chosen one

The Chosen One is a character marked by destiny, prophecy, or fate. They are often born special or unknowingly carry a power that makes them central to the story’s conflict. At first, the Chosen One may feel overwhelmed, unprepared, or even unwilling to accept their role.

Their journey usually involves training, loss, self-doubt, and finally embracing who they are meant to be. This stereotype resonates because it mirrors our own desire to feel meaningful and special.

Examples: Harry Potter, Naruto Uzumaki, Neo

2. The reluctant hero

The Reluctant Hero doesn’t chase glory or recognition. In fact, they often resist the call to adventure entirely. They might want a quiet life, personal peace, or simply to be left alone.

What defines this character is growth. Over time, they learn that avoiding responsibility can sometimes be more dangerous than facing it. Their heroism feels authentic because it’s born out of necessity, not ego. Audiences love them because they feel human and relatable.

Examples: Frodo Baggins, Peter Parker, Katniss Everdeen

3. The anti-hero

Anti-heroes break the traditional rules of heroism. They may lie, kill, manipulate, or act selfishly, yet we still root for them. This stereotype thrives in morally complex stories where right and wrong aren’t clearly defined.

They often reflect society’s darker truths and question whether good intentions always lead to good outcomes. Anti-heroes are fascinating because they force audiences to confront uncomfortable moral questions.

Examples: Deadpool, Light Yagami, Geralt of Rivia

4. The pure hero

The Pure Hero represents idealism, justice, and moral clarity. They believe in doing the right thing even when it’s difficult or unpopular. This stereotype is often criticized as “too perfect,” but when written well, it symbolizes hope.

Their real struggle usually isn’t physical; it’s maintaining goodness in a corrupt world. They inspire others simply by existing.

Examples: Superman, Captain America, Tanjiro Kamado

5. The villain mastermind

This character is intelligent, calculated, and always three steps ahead. The Villain Mastermind doesn’t rely solely on brute force; they manipulate people, systems, and emotions.

Their strength lies in strategy and psychological warfare. They are terrifying because they expose the hero’s weaknesses long before the final battle.

Examples: Loki, Johan Liebert, Lex Luthor

6. The tragic villain

The Tragic Villain wasn’t always evil. They were shaped by trauma, injustice, betrayal, or loss. Their story often makes audiences feel sympathy even when their actions are unforgivable.

This stereotype explores how pain can twist good intentions into destructive choices. Redemption is sometimes possible, but not guaranteed.

Examples: Darth Vader, Obito Uchiha, Magneto

7. The evil-for-evil’s sake villain

This villain thrives on chaos and destruction. They don’t need a tragic backstory or justification; they simply enjoy being evil.

They exist to challenge order and sanity, often acting as a force of pure opposition. These characters raise the stakes and keep stories unpredictable.

Examples: Joker, Frieza, Voldemort

8. The mentor

The Mentor is the guiding force behind the hero’s growth. They provide wisdom, training, and emotional support. Often, they know more than they reveal.

Their role is temporary by design. Eventually, the hero must stand alone, which is why mentors often die or step aside.

Examples: Dumbledore, Obi-Wan Kenobi, Jiraiya

9. The loyal best friend

This character provides emotional grounding. They may lack the hero’s power or status, but their loyalty is unwavering.

They remind the protagonist of their humanity and often act as moral support during the darkest moments.

Examples: Ron Weasley, Samwise Gamgee, Usopp

10. The comic relief

Comic relief characters break the tension and bring humor into intense narratives. Their jokes and antics help audiences breathe during heavy moments.

When written well, they also possess emotional depth and surprising bravery.

Examples: Sokka, Genie, Olaf

11. The love interest

More than just romance, this character often represents emotional growth. They challenge the protagonist, influence their decisions, and raise emotional stakes.

A strong love interest has agency and purpose beyond romance.

Examples: Elizabeth Bennet, Hinata Hyuga, Rose

12. The femme fatale

The Femme Fatale is intelligent, seductive, and dangerous. She uses charm as a weapon and often blurs the line between ally and enemy.

Modern stories give this stereotype more autonomy and depth, transforming her into a symbol of power rather than manipulation alone.

Examples: Catwoman, Black Widow

13. The strong, silent type

This character speaks through actions rather than words. Their quiet nature often hides deep emotional pain or strong moral values.

They are compelling because they invite curiosity; audiences read meaning into every glance and gesture.

Examples: Levi Ackerman, John Wick

14. The innocent

The Innocent believes in goodness, kindness, and hope. They often act as a moral compass for darker characters.

Their purity can change others—or tragically be crushed by reality.

Examples: Luna Lovegood, Forrest Gump

15. The genius

This stereotype is defined by extraordinary intelligence. They solve complex problems that others can’t, but often struggle socially or emotionally.

Their challenge lies in connecting with people, not ideas.

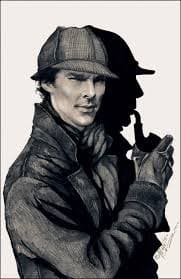

Examples: Sherlock Holmes, L, Tony Stark

16. The mad scientist

The Mad Scientist is driven by obsession and ambition, often believing that the end justifies the means. Unlike the Genius, this character is willing to cross ethical boundaries in pursuit of knowledge, power, or innovation.

Their experiments may begin with noble intentions, curing disease, advancing humanity, but slowly spiral into chaos. Despite their extremes, some Mad Scientists are portrayed with humor or tragic depth, making them unsettling yet fascinating figures.

Examples: Dr. Frankenstein, Rick Sanchez

17. The underdog

The Underdog is defined not by talent or privilege, but by determination and resilience. They begin their journey at a clear disadvantag,e whether it’s a lack of strength, status, confidence, or resources. What sets them apart is their refusal to quit, even when the odds are stacked against them.

These characters remind us that growth comes from effort, failure, and perseverance rather than natural ability alone. The Underdog’s arc often emphasizes self-belief, discipline, and the power of support systems like mentors and friends.

Examples: Rocky Balboa, Izuku “Deku” Midoriya

18. The rebel

The Rebel stands against authority, tradition, and oppressive systems. They refuse to accept the world as it is and actively challenge rules they see as unjust. Rebels are often catalysts for change, inspiring others to question long-standing norms and power structures.

Their actions often come at great personal cost, reinforcing the idea that change is never easy. The Rebel resonates strongly in dystopian and political narratives, symbolizing hope, resistance, and the human desire for autonomy.

Examples: Katniss Everdeen, V (V for Vendetta)

19. The tyrannical leader

The Tyrant Leader represents power corrupted by ego, fear, and control. These characters rule through intimidation, cruelty, and manipulation, often convinced that their authority is absolute and justified. They see dissent as a threat and respond with violence or punishment.

What makes Tyrants effective villains is their belief in their own righteousness. Tyrant Leaders serve as cautionary figures, reminding audiences of the consequences of unchecked power and the importance of accountability.

Examples: Joffrey Baratheon, Fire Lord Ozai

20. The sidekick

The Sidekick may not be the strongest or smartest character, but they are often the emotional backbone of the story. Loyal, supportive, and brave in their own way, sidekicks help ground the hero, providing encouragement, humor, and perspective during moments of doubt.

Many modern stories allow sidekicks to grow, proving they are more than just background support. Their evolution from helper to hero highlights themes of confidence, growth, and hidden potential.

Examples: Robin, Pikachu

21. The fallen hero

The Fallen Hero begins their journey as someone admired, trusted, or even idolized. They possess talent, moral authority, or heroic ideals, but something within them cracks. Pride, fear, jealousy, or manipulation push them toward choices that betray who they once were.

Some Fallen Heroes descend completely into darkness, while others seek redemption, forcing audiences to confront difficult questions about forgiveness and responsibility. Their arcs remind us that heroism is fragile and must be constantly chosen.

Examples: Anakin Skywalker, Jaime Lannister

22. The Mary Sue / Gary Stu

The Mary Sue or Gary Stu is defined by near-perfection without effort. These characters excel at everything they attempt, face minimal consequences, and are universally admired even by former enemies. Conflicts rarely challenge them in meaningful ways, making victories feel inevitable rather than earned.

This trope can work when used intentionally, such as for satire, wish fulfillment, or mythic storytelling. The key difference lies in whether the character’s perfection serves a narrative purpose.

Examples: Rey, Bella Swan, Wesley Crusher

23. The ice queen/king

The Ice Queen or King is emotionally distant, composed, and often intimidating. They keep people at arm’s length, not out of cruelty, but as a defense mechanism. Past trauma, fear of vulnerability, or societal expectations have taught them that emotional detachment equals safety.

When Ice characters finally open up, their emotional moments carry exceptional impact. They represent the idea that strength doesn’t mean emotional isolation and that connection is not weakness.

Examples: Elsa, Mr. Darcy

24. The outsider

The Outsider exists on the fringes of society, never fully accepted by any group. This separation may be physical, emotional, cultural, or psychological. Their story is often rooted in loneliness and self-questioning as they search for belonging and identity.

Because Outsiders aren’t absorbed into social norms, they often see truths others ignore. Their perspective allows them to critique society, challenge hypocrisy, or expose injustice.

Examples: Edward Scissorhands, Gaara

25. The manipulator

The Manipulator wields power not through strength or authority, but through psychological control. They understand people’s fears, desires, and weaknesses and exploit them subtly. Often operating behind the scenes, they influence events without drawing attention to themselves.

They embody the danger of intellect divorced from empathy and highlight how control can be more destructive than brute force.

Examples: Aizen, Littlefinger

26. The protective parent figure

The Protective Parent Figure serves as a source of guidance, comfort, and moral stability. Whether biologically related or not, they offer emotional safety and wisdom, often stepping in when others cannot. Their love is unconditional, patient, and deeply rooted in responsibility.

These characters frequently make sacrifices, sometimes even giving their lives to protect those they care for. They symbolize the enduring power of mentorship and chosen family.

Examples: Uncle Iroh, Molly Weasley

27. The wild card

The Wild Card thrives on unpredictability. Their actions are spontaneous, chaotic, and often contradictory, making them impossible to control or fully understand. They can shift from ally to threat in an instant, keeping both characters and audiences on edge.

Wild Cards inject energy and tension into stories. Because their motives are unclear, every scene involving them feels risky and exciting. Beneath the chaos, however, they often follow their own internal logic or personal code.

Examples: Hisoka, Jack Sparrow

28. The redemption arc character

The Redemption Arc Character begins as morally flawed, antagonistic, or outright villainous. Over time, they confront the consequences of their actions and choose to change not because they are forgiven, but because they accept responsibility.

What makes redemption compelling is struggle. True redemption is painful, slow, and often incomplete. These characters must live with their past even as they work to become better.

Examples: Zuko, Severus Snape

29. The broken genius

The Broken Genius pairs exceptional intellect with serious emotional damage. Trauma, addiction, mental health struggles, or self-destructive tendencies plague these characters, making their brilliance both a gift and a burden.

Their intelligence often isolates them, intensifying feelings of emptiness or disconnection. Stories featuring Broken Geniuses explore the cost of brilliance.

Examples: Dr. House, BoJack Horseman

30. The narrator/observer

The Narrator or Observer does not always drive the plot, but profoundly shapes how the story is understood. Through their voice, perspective, or commentary, they guide the audience’s emotional and moral interpretation of events.

Observers often serve as witnesses rather than heroes, allowing the focus to remain on others while still offering insight, reflection, or judgment.

Examples: Nick Carraway, Death (The Book Thief)

31. The trickster

The Trickster thrives on chaos, wit, and subversion. They break rules not just for fun, but to expose how fragile and artificial those rules really are. Often armed with humor, deception, and clever wordplay, Tricksters undermine authority figures by making them look foolish rather than confronting them directly.

Beneath the laughter, the Trickster often serves as a truth-teller. They reveal hypocrisy, hidden motives, and uncomfortable realities that others are too afraid—or too invested—to address.

Examples: Loki (mythology), Bugs Bunny, Hisoka

32. The caregiver

The Caregiver’s primary motivation is love expressed through action. They nurture, protect, and emotionally sustain others, often placing the needs of loved ones above their own. In stories filled with conflict and danger, Caregivers provide warmth, stability, and moral grounding.

Caregivers remind audiences that kindness is not passive; it is a powerful, deliberate choice.

Examples: Samwise Gamgee, Marge Simpson, Florence Nightingale–type figures

33. The orphan

The Orphan archetype goes far beyond the literal absence of parents. It represents emotional vulnerability, independence, and the longing for connection.

Orphan characters often mature early, forced to navigate the world without guidance or protection. This lack of family becomes a driving force in their story. Orphans may seek belonging, justice, or purpose, often forming “found families” along the way.

Examples: Batman, Harry Potter, Anne Shirley

34. The everyman/everywoman

The Everyman or Everywoman represents the ordinary person caught in extraordinary circumstances. They lack special powers, grand destinies, or exceptional skills. Instead, they rely on common sense, perseverance, and relatability.

The Everyman reminds us that heroism can emerge from everyday people.

Examples: Bilbo Baggins, Jim Halpert, Arthur Dent

35. The rags-to-riches character

The Rags-to-Riches arc is a classic transformation story rooted in aspiration and hope. Beginning in poverty, obscurity, or insignificance, this character rises through determination, talent, ambition, or luck. Their external success often mirrors an internal evolution.

However, not all Rags-to-Riches stories are celebratory. Some explore the cost of success, questioning whether wealth or status comes at the expense of integrity, relationships, or identity.

Examples: Aladdin, Jay Gatsby, Rocky Balboa

36. The corrupt official

The Corrupt Official abuses authority for personal gain, often hiding behind charm, bureaucracy, or moral rhetoric. Unlike overt villains, they operate within the system, making their corruption feel disturbingly realistic.

They are powerful antagonists because audiences recognize them from real life.

Examples: President Snow, Dolores Umbridge, Senator Palpatine (early)

37. The idealist

The Idealist believes deeply in the possibility of a better world. Guided by principles, hope, and moral clarity, they fight for long-term change even when mocked.

The Idealist’s greatest challenge is reality. Compromise, failure, and moral gray areas test their beliefs, forcing them to evolve without losing their core values. When written well, Idealists inspire audiences to question cynicism and imagine alternatives.

Examples: Don Quixote, Steven Universe, Captain America (early)

38. The cynic

The Cynic expects disappointment and shields themselves with sarcasm, detachment, or skepticism. Often shaped by betrayal, loss, or repeated failure, they reject hope as a defense mechanism.

Despite their pessimism, Cynics are rarely emotionless. Their bitterness usually masks deep vulnerability and unhealed wounds. Growth arcs for Cynics often involve rediscovering trust or hope not through grand gestures, but small, meaningful connections.

Examples: Rick Sanchez, Dr. House, Daria Morgendorffer

39. The outlaw

The Outlaw lives outside societal rules, either by choice or circumstance. They reject authority, tradition, or legal systems, carving their own moral code. Sometimes they are rebels with a cause; other times, survivors forced into the margins.

Outlaws embody freedom and defiance but also moral ambiguity. Their actions may challenge unjust systems or simply reflect personal survival.

Examples: Robin Hood, Han Solo, Jesse Pinkman

40. The seeker

The Seeker is defined by a quest for meaning rather than conquest. Their journey may involve travel, self-discovery, or spiritual awakening, but the true transformation is internal.

Seekers ask life’s biggest questions: Who am I? What matters? Where do I belong?

Success is measured not by what they gain, but by who they become.

Examples: Siddhartha, Moana, Pi Patel

41. The protector

The Protector fights not for glory, honor, or conquest, but out of love and fear of loss. Unlike a typical warrior, the Protector does not seek conflict; they endure it because they believe they must.

The Protector may begin making decisions for others rather than with them, justifying harmful choices as necessary sacrifices. Their arc often explores the painful truth that love does not grant ownership and that safety cannot come at the cost of another’s freedom.

Examples: Joel (The Last of Us), Mikasa Ackerman, Sarah Connor

42. The fanatic

The Fanatic is driven by absolute belief. Whether rooted in religion, politics, nationalism, or ideology, their worldview is rigid and uncompromising. They divide the world into right and wrong, pure and corrupt, believer and enemy—leaving no room for nuance.

They exist to show how conviction, when unchecked, can become inhuman.

Examples: Javert, Silco, The High Sparrow

43. The fallen mentor

The Fallen Mentor was once a figure of wisdom, guidance, and moral clarity. Over time, disillusionment, fear, pride, or temptation corrodes their ideals. Their fall often mirrors the hero’s path, offering a grim vision of what the protagonist could become under different choices.

Unlike outright villains, Fallen Mentors are tragic. They know what goodness looks like—and choose to abandon or distort it.

Examples: Saruman, Gellert Grindelwald, Professor Snape (early perception)

44. The savior complex character

This character believes they are personally responsible for saving others, even when no one asked them to. Driven by guilt, fear, or ego, they take on burdens that are not theirs to carry. Their intentions may be noble, but their actions often strip others of agency.

Their arc asks a difficult question: Who decides what “saving” really means?

Examples: Wanda Maximoff, Superman (certain arcs), Light Yagami

45. The observer genius

The Observer Genius watches more than they speak. Highly analytical and emotionally reserved, they excel at reading micro-expressions, patterns, and behavioral clues. While others react, they calculate.

They are mirrors to others, yet rarely see themselves.

Examples: L (Death Note), Sherlock (BBC), Spencer Reid

46. The spoiled heir

Born into wealth, power, or prestige, the Spoiled Heir begins their story insulated from consequences. Entitlement, arrogance, or ignorance defines their early behavior, not necessarily out of cruelty, but lack of perspective.

When stripped of privilege or forced to face real responsibility, they must decide whether to mature or collapse.

Examples: Prince Zuko (early), Draco Malfoy, Kuzco

47. The moral compass

The Moral Compass serves as the ethical anchor of the story. They consistently remind others of right and wrong, even when it’s inconvenient or dangerous. Their strength lies not in power, but in unwavering integrity.

Often calm, kind, and principled, they influence decisions simply by existing. When the Moral Compass is lost through death, betrayal, or corruption, the story often enters its darkest phase, signaling moral collapse.

Examples: Mufasa, Atticus Finch, Uncle Ben

48. The survivor

The Survivor has endured unimaginable trauma and continues to live—sometimes out of necessity rather than hope. Survival itself becomes an act of defiance. These characters are often hardened, wary, and emotionally scarred.

Unlike traditional heroes, Survivors are not chasing victory or glory. Their stories focus on endurance, healing, and the long-term effects of trauma.

Examples: Katniss Everdeen, Ellie (The Last of Us), Lara Croft

49. The strategist

The Strategist wins battles before they begin. Calm under pressure and capable of long-term planning, they excel in warfare, politics, and psychological conflict. Where others react emotionally, Strategists think several steps ahead.

However, their reliance on logic can create distance from those around them. They may view people as pieces on a board, struggling with guilt when plans require sacrifice.

Examples: Lelouch Lamperouge, Erwin Smith, Tyrion Lannister

50. The shadow self

The Shadow Self is the protagonist’s dark reflection—the embodiment of traits taken to their extreme. They show what the hero could become if they surrender to fear, anger, or obsession.

This stereotype exists to force self-reflection. Confronting the Shadow Self is less about defeating an enemy and more about rejecting a path. These conflicts are deeply personal, often emotional rather than physical.

Examples: Voldemort vs Harry, Killmonger vs T’Challa, Sasuke vs Naruto

Character stereotypes are the building blocks of storytelling. While they may start as familiar templates, great writers transform them into complex, memorable characters that feel real and relatable.

Whether it’s a reluctant hero, a tragic villain, or a loyal best friend, these stereotypes continue to evolve just like the stories we love. When used thoughtfully, they don’t limit creativity; they launch it.

So the next time you recognize a character instantly, smile, you’re witnessing storytelling tradition at work.

If you’ve written your own kick-ass characters, publish them in a book with PaperTrue’s self-publishing services today!

Read more: