- A List of Writing Contests in 2022 | Exciting Prizes!

- Em Dash vs. En Dash vs. Hyphen: When to Use Which

- Book Proofreading 101: The Beginner’s Guide

- Screenplay Editing: Importance, Cost, & Self-Editing Tips

- Screenplay Proofreading: Importance, Process, & Cost

- Script Proofreading: Rates, Process, & Proofreading Tips

- Manuscript Proofreading | Definition, Process & Standard Rates

- Tips to Write Better if English Is Your Second Language

- Novel Proofreading | Definition, Significance & Standard Rates

- Top 10 Must-Try Writing Prompt Generators in 2024

- 100+ Creative Writing Prompts for Masterful Storytelling

- Top 10 eBook Creator Tools in 2024: Free & Paid

- 50 Timeless and Unforgettable Book Covers of All Time

- What Is Flash Fiction? Definition, Examples & Types

- 80 Enchanting Christmas Writing Prompts for Your Next Story

- Top 10 Book Review Clubs of 2025 to Share Literary Insights

- 2024’s Top 10 Self-Help Books for Better Living

- Writing Contests 2023: Cash Prizes, Free Entries, & More!

- What Is a Book Teaser and How to Write It: Tips and Examples

- Audiobook vs. EBook vs. Paperback in 2024: (Pros & Cons)

- How to Get a Literary Agent in 2024: The Complete Guide

- Alpha Readers: Where to Find Them and Alpha vs. Beta Readers

- Author Branding 101: How to Build a Powerful Author Brand

- A Guide on How to Write a Book Synopsis: Steps and Examples

- How to Write a Book Review (Meaning, Tips & Examples)

- 50 Best Literary Agents in the USA for Authors in 2024

- Building an Author Website: The Ultimate Guide with Examples

- Top 10 Paraphrasing Tools for All (Free & Paid)

- Top 10 Book Editing Software in 2024 (Free & Paid)

- What Are Large Language Models and How They Work: Explained!

- Top 10 Hardcover Book Printing Services [Best of 2024]

- 2024’s Top 10 Setting Generators to Create Unique Settings

- Different Types of Characters in Stories That Steal the Show

- Top 10 Screenplay & Scriptwriting Software (Free & Paid)

- 10 Best AI Text Generators of 2024: Pros, Cons, and Prices

- Top 10 Must-Try Character Name Generators in 2024

- 10 Best AI Text Summarizers in 2024 (Free & Paid)

- 11 Best Story Structures for Writers (+ Examples!)

- How to Write a Book with AI in 2024 (Free & Paid Tools)

- Writing Contests 2024: Cash Prizes & Free Entries!

- Patchwork Plagiarism: Definition, Types, & Examples

- Simple Resume Formats for Maximum Impact With Samples

- What Is a Complement in a Sentence? (Meaning, Types & Examples)

- What are Clauses? Definition, Meaning, Types, and Examples

- Persuasive Writing Guide: Techniques & Examples

- How to Paraphrase a Text (Examples + 10 Strategies!)

- A Simple Proofreading Checklist to Catch Every Mistake

- Top 10 AI Resume Checkers for Job Seekers (Free & Paid)

- 20 Best Comic Book Covers of All Time!

- How to Edit a Book: A Practical Guide with 7 Easy Steps

- How to Write an Autobiography (7 Amazing Strategies!)

- How to Publish a Comic Book: Nine Steps & Publishing Costs

- Passive and Active Voice (Meaning, Examples & Uses)

- How to Publish a Short Story & Best Publishing Platforms

- What Is Expository Writing? Types, Examples, & 10 Tips

- 10 Best Introduction Generators (Includes Free AI Tools!)

- Creative Writing: A Beginner’s Guide to Get Started

- How to Sell Books Online (Steps, Best Platforms & Tools)

- Top 10 Book Promotion Services for Authors (2025)

- 15 Different Types of Poems: Examples & Insight into Poetic Styles

- 10 Best Book Writing Apps for Writers 2025: Free & Paid!

- Top 10 AI Humanizers of 2025 [Free & Paid Tools]

- How to Write a Poem: Step-by-Step Guide to Writing Poetry

- 100+ Amazing Short Story Ideas to Craft Unforgettable Stories

- The Top 10 Literary Devices: Definitions & Examples

- Top 10 AI Translators for High-Quality Translation in 2025

- Top 10 AI Tools for Research in 2025 (Fast & Efficient!)

- 50 Best Essay Prompts for College Students in 2025

- Top 10 Book Distribution Services for Authors in 2025

- Top 10 Book Title Generators of 2025

- Best Fonts and Sizes for Books: A Complete Guide

- What Is an Adjective? Definition, Usage & Examples

- How to Track Changes in Google Docs: A 7-Step Guide

- Best Book Review Sites of 2025: Top 10 Picks

- Parts of a Book: A Practical, Easy-to-Understand Guide

- What Is an Anthology? Meaning, Types, & Anthology Examples

- How to Write a Book Report | Steps, Examples & Free Template

- 10 Best Plot Generators for Engaging Storytelling in 2025

- 30 Powerful Poems About Life to Inspire and Uplift You

- What Is a Poem? Poetry Definition, Elements, & Examples

- Metonymy: Definition, Examples, and How to Use It In Writing

- How to Write a CV with AI in 9 Steps (+ AI CV Builders)

- What Is an Adverb? Definition, Types, & Practical Examples

- How to Create the Perfect Book Trailer for Free

- Top 10 Book Publishing Companies in 2025

- 14 Punctuation Marks: A Guide on How to Use with Examples!

- Translation Services: Top 10 Professional Translators (2025)

- 10 Best Free Online Grammar Checkers: Features and Ratings

- 30 Popular Children’s Books Teachers Recommend in 2025

- 10 Best Photobook Makers of 2025 We Tested This Year

- Top 10 Book Marketing Services of 2025: Features and Costs

- Top 10 Book Printing Services for Authors in 2025

- 10 Best AI Detector Tools in 2025

- Audiobook Marketing Guide: Best Strategies, Tools & Ideas

- 10 Best AI Writing Assistants of 2025 (Features + Pricing)

- How to Write a Book Press Release that Grabs Attention

- 15 Powerful Writing Techniques for Authors in 2025

- Generative AI: Types, Impact, Advantages, Disadvantages

- Top 101 Bone-Chilling Horror Writing Prompts

- 25 Figures of Speech Simplified: Definitions and Examples

- Top 10 AI Rewriters for Perfect Text in 2025 (Free & Paid)

- Best EBook Cover Design Services of 2025 for Authors

- Writing Contests 2025: Cash Prizes, Free Entries, and More!

- Top 10 Book Writing Software, Websites, and Tools in 2025

- National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo)

- Best Horror Books of All Time (Must-Read List)

- Best Book Trailer Services

- Your Guide to the Best eBook Readers in 2026

- 10 Best Punctuation Checkers for Error-Free Text (2026)

- Master Circumlocution: Definition, Examples & Literary Uses

- Best Historical Fiction Books: 30 Must-Read Novels

- Best 101 Greatest Fictional Characters of All Time

- Writing Contests 2026: Free Entries and Cash Prizes!

- What is a Book Copyright Page?

- Final Checklist: Is My Article Ready for Submitting to Journals?

- 8 Pre-Publishing Steps to Self-Publish Your Book

- 7 Essential Elements of a Book Cover Design

- How to Copyright Your Book in the US, UK, & India

- Beta Readers: Why You Should Know About Them in 2024

- How to Publish a Book in 2024: Essential Tips for Beginners

- Book Cover Design Basics: Tips & Best Book Cover Ideas

- Why and How to Use an Author Pen Name: Guide for Authors

- How to Format a Book in 2025: 7 Tips for Book Formatting

- What is Manuscript Critique? Benefits, Process, & Cost

- 10 Best Ghostwriting Services for Authors in 2025

- ISBN Guide 2025: What Is an ISBN and How to Get an ISBN

- Best Manuscript Editing Services of 2025

- Best Manuscript Critique Services (2026): Top 10 Picks

- How To Format a Book in Google Docs (Step-by-Step)

- How to Hire a Book Editor in 5 Practical Steps

- Self-Publishing Options for Writers

- How to Promote Your Book Using a Goodreads Author Page

- 7 Essential Elements of a Book Cover Design

- What Makes Typesetting a Pre-Publishing Essential for Every Author?

- 4 Online Publishing Platforms To Boost Your Readership

- Typesetting: An Introduction

- Quick Guide to Novel Editing (with a Self-Editing Checklist)

- Self-Publishing vs. Traditional Publishing: 2024 Guide

- How to Publish a Book in 2024: Essential Tips for Beginners

- How to Publish a Book on Amazon: 8 Easy Steps [2024 Update]

- What are Print-on-Demand Books? Cost and Process in 2024

- What Are the Standard Book Sizes for Publishing Your Book?

- How to Market Your Book on Amazon to Maximize Sales in 2024

- Top 10 Hardcover Book Printing Services [Best of 2024]

- How to Find an Editor for Your Book in 8 Steps (+ Costs!)

- What Is Amazon Self-Publishing? Pros, Cons & Key Insights

- Manuscript Editing in 2024: Elevating Your Writing for Success

- Know Everything About How to Make an Audiobook

- A Simple 14-Point Self-Publishing Checklist for Authors

- How to Write an Engaging Author Bio: Tips and Examples

- Book Cover Design Basics: Tips & Best Book Cover Ideas

- How to Publish a Comic Book: Nine Steps & Publishing Costs

- Why and How to Use an Author Pen Name: Guide for Authors

- How to Sell Books Online (Steps, Best Platforms & Tools)

- A Simple Guide to Select the Best Self-Publishing Websites

- 10 Best Book Cover Design Services of 2025: Price & Ratings

- How Much Does It Cost to Self-Publish a Book in 2025?

- Quick Guide to Book Editing [Complete Process & Standard Rates]

- How to Distinguish Between Genuine and Fake Literary Agents

- What is Self-Publishing? Everything You Need to Know

- How to Copyright a Book in 2025 (Costs + Free Template)

- The Best eBook Conversion Services of 2025: Top 10 Picks

- 10 Best Self-Publishing Companies of 2025: Price & Royalties

- 10 Best Photobook Makers of 2025 We Tested This Year

- Book Cover Types: Formats, Bindings & Styles

- ISBN Guide 2025: What Is an ISBN and How to Get an ISBN

- A Beginner’s Guide on How to Self Publish a Book (2025)

- Index in a Book: Definition, Purpose, and How to Use It

- How to Publish a Novel: Easy Step-By-Step Guide

- How to Design a Book Cover: From Concept to Covers That Sell

- 8 Tips To Write Appealing Query Letters

- Self-Publishing vs. Traditional Publishing: 2024 Guide

- How to Publish a Book in 2024: Essential Tips for Beginners

- What are Print-on-Demand Books? Cost and Process in 2024

- How to Write a Query Letter (Examples + Free Template)

- Third-person Point of View: Definition, Types, Examples

- How to Write an Engaging Author Bio: Tips and Examples

- How to Publish a Comic Book: Nine Steps & Publishing Costs

- Top 10 Book Publishing Companies in 2025

- 10 Best Photobook Makers of 2025 We Tested This Year

- Book Cover Types: Formats, Bindings & Styles

- ISBN Guide 2025: What Is an ISBN and How to Get an ISBN

- Index in a Book: Definition, Purpose, and How to Use It

- How to Publish a Novel: Easy Step-By-Step Guide

- How to start your own online publishing company?

- How to Design a Book Cover: From Concept to Covers That Sell

- How to Create Depth in Characters

- Starting Your Book With a Bang: Ways to Catch Readers’ Attention

- Research for Fiction Writers: A Complete Guide

- Short stories: Do’s and don’ts

- How to Write Dialogue: 7 Rules, 5 Tips & 65 Examples

- What Are Foil and Stock Characters? Easy Examples from Harry Potter

- How To Write Better Letters In Your Novel

- On Being Tense About Tense: What Verb Tense To Write Your Novel In

- How To Create A Stellar Plot Outline

- How to Punctuate Dialogue in Fiction

- On Being Tense about Tense: Present Tense Narratives in Novels

- The Essential Guide to Worldbuilding [from Book Editors]

- What Is Point of View? Definition, Types, & Examples in Writing

- How to Create Powerful Conflict in Your Story | Useful Examples

- How to Write a Book: A Step-by-Step Guide

- How to Write a Short Story in 6 Simple Steps

- How to Write a Novel: 8 Steps to Help You Start Writing

- What Is a Stock Character? 150 Examples from 5 Genres

- Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey: Worksheet & Examples

- Novel Outline: A Proven Blueprint [+ Free Template!]

- Character Development: 7-Step Guide for Writers

- What Is NaNoWriMo? Top 7 Tips to Ace the Writing Marathon

- What Is the Setting of a Story? Meaning + 7 Expert Tips

- What Is a Blurb? Meaning, Examples & 10 Expert Tips

- What Is Show, Don’t Tell? (Meaning, Examples & 6 Tips)

- How to Write a Book Summary: Example, Tips, & Bonus Section

- How to Write a Book Description (Examples + Free Template)

- 10 Best Free AI Resume Builders to Create the Perfect CV

- A Complete Guide on How to Use ChatGPT to Write a Resume

- 10 Best AI Writer Tools Every Writer Should Know About

- How to Write a Book Title (15 Expert Tips + Examples)

- 100 Novel and Book Ideas to Start Your Book Writing Journey

- Exploring Writing Styles: Meaning, Types, and Examples

- Mastering Professional Email Writing: Steps, Tips & Examples

- How to Write a Screenplay: Expert Tips, Steps, and Examples

- Business Proposal Guide: How to Write, Examples and Template

- Different Types of Resumes: Explained with Tips and Examples

- How to Create a Memorable Protagonist (7 Expert Tips)

- How to Write an Antagonist (Examples & 7 Expert Tips)

- Writing for the Web: 7 Expert Tips for Web Content Writing

- 10 Best AI Text Generators of 2024: Pros, Cons, and Prices

- What are the Parts of a Sentence? An Easy-to-Learn Guide

- What Is Climax Of A Story & How To Craft A Gripping Climax

- What Is a Subject of a Sentence? Meaning, Examples & Types

- Object of a Sentence: Your Comprehensive Guide

- What Is First-Person Point of View? Tips & Practical Examples

- Second-person Point of View: What Is It and Examples

- 10 Best AI Essay Outline Generators of 2024

- Third-person Point of View: Definition, Types, Examples

- The Importance of Proofreading: A Comprehensive Overview

- Patchwork Plagiarism: Definition, Types, & Examples

- Simple Resume Formats for Maximum Impact With Samples

- The Ultimate Guide to Phrases In English – Types & Examples

- Modifiers: Definition, Meaning, Types, and Examples

- What are Clauses? Definition, Meaning, Types, and Examples

- Persuasive Writing Guide: Techniques & Examples

- What Is a Simile? Meaning, Examples & How to Use Similes

- Mastering Metaphors: Definition, Types, and Examples

- How to Publish a Comic Book: Nine Steps & Publishing Costs

- Essential Grammar Rules: Master Basic & Advanced Writing Skills

- Benefits of Using an AI Writing Generator for Editing

- Hyperbole in Writing: Definition and Examples

- 15 Best ATS-Friendly ChatGPT Prompts for Resumes in 2025

- How to Write a Novel in Past Tense? 3 Steps & Examples

- 10 Best Spell Checkers of 2025: Features, Accuracy & Ranking

- Foil Character: Definition, History, & Examples

- 5 Key Elements of a Short Story: Essential Tips for Writers

- How to Write a Children’s Book: An Easy Step-by-Step Guide

- How To Write a Murder Mystery Story

- What Is an Adjective? Definition, Usage & Examples

- Metonymy: Definition, Examples, and How to Use It In Writing

- Fourth-Person Point of View: A Unique Narrative Guide

- How to Write a CV with AI in 9 Steps (+ AI CV Builders)

- What Is an Adverb? Definition, Types, & Practical Examples

- How to Write A Legal Document in 6 Easy Steps

- 10 Best AI Story Generators in 2025: Write Captivating Tales

- How to Introduce a Character Effectively

- What is Rhetoric and How to Use It in Your Writing

- How to Write a Powerful Plot in 12 Steps

- How to Make Money as a Writer: Your First $1,000 Guide

- How to Write SEO Content: Tips for SEO-Optimized Content

- Types of Introductions and Examples

- What is a Cliffhanger? Definition, Examples, & Writing Tips

- How to Write Cliffhangers that Keep Readers Hooked!

- How to Write a Romance Novel: Step-by-Step Guide

- Top 10 Writing Tips from Famous Authors

- 10 Best Ghostwriting Services for Authors in 2025

- What is Ghostwriting? Meaning and Examples

- How to Become a Ghostwriter: Complete Career Guide

- How to Write a Speech that Inspires (With Examples)

- Theme of a Story | Meaning, Common Themes & Examples

- 10 Best AI Writing Assistants of 2025 (Features + Pricing)

- Generative AI: Types, Impact, Advantages, Disadvantages

- Worldbuilding Questions and Templates (Free)

- How to Avoid Plagiarism in 2025 (10 Effective Strategies!)

- How to Create Marketing Material

- What Is Worldbuilding? Steps, Tips, and Examples

- What is Syntax in Writing: Definition and Examples

- What is a Subplot? Meaning, Examples & Types

- Writing Challenges Every Writer Should Take

- What Is a Memoir? Definition, Examples, and Tips

- What Is Fiction? Definition, Types & Examples

- What Is Science Fiction? Meaning, Examples, and Types

- 50 Character Stereotypes: The Ultimate List!

- 50 Novel Writing Prompts (Categorized by Genre)

- 50 Haiku Writing Prompts For Your Inner Poet

- Direct Characterization: Definition, Examples & Comparison

- Indirect Characterization: Meaning, Examples & Writing Tips

- Direct vs Indirect Characterization: What’s the Difference

- How to Write Epic Fantasy

- 50 Non-fiction Writing Prompts For Your Inner Writer

- Master Circumlocution: Definition, Examples & Literary Uses

- How to Write a Good Villain (With Examples)

- How to Avoid AI Detection in 2026 (6 Proven Techniques!)

- How to Write a Cookbook: Step-by-Step Guide

Still have questions? Leave a comment

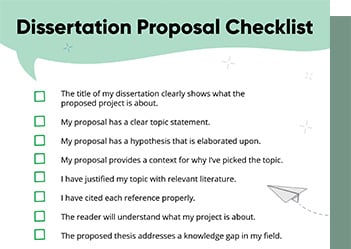

Checklist: Dissertation Proposal

Enter your email id to get the downloadable right in your inbox!

[contact-form-7 id="12425" title="Checklist: Dissertation Proposal"]

Examples: Edited Papers

Enter your email id to get the downloadable right in your inbox!

[contact-form-7 id="12426" title="Examples: Edited Papers"]Need

Editing and

Proofreading Services?

Indirect Characterization: Meaning, Examples & Writing Tips

Jan 16, 2026

Jan 16, 2026 7

min read

7

min read

- Tags: Character, Fiction Writing, Writers

Characters are the heart of every story, but the most memorable ones are rarely described outright. Instead of being told who a character is, readers often discover it through subtle clues woven into the narrative. This technique is known as indirect characterization.

By revealing personality through actions, dialogue, thoughts, and interactions, writers create deeper, more realistic characters. In this article, you’ll learn what indirect characterization is, how it works, why it matters, and how both readers and writers can analyze and use it effectively.

Bring Your Characters To Life. Publish Your Book Now! Get Started

What is indirect characterization?

Indirect characterization is a literary technique where a writer reveals a character’s personality without directly stating it. Unlike direct characterization, instead of telling readers who a character is, the author shows it through behavior, dialogue, thoughts, choices, and interactions.

In simple terms, indirect characterization lets readers figure out a character on their own.

Indirect characterization definition

Indirect characterization is the process of developing a character by implying traits through actions, speech, thoughts, appearance, and reactions, rather than explicitly describing them.

Why writers use indirect characterization

Indirect characterization is powerful because it:

- Makes characters feel real and complex

- Engages readers more deeply

- Encourages interpretation and emotional connection

- Follows the classic writing rule: “Show, don’t tell.”

Instead of saying “She was brave,” the writer shows her walking into danger despite fear.

How indirect characterization works (with examples)

Writers typically use five main methods to create indirect characterization.

1. Actions

What a character does often reveals who they are.

Example of indirect characterization:

Instead of saying “Ravi was kind,” the story shows Ravi giving his lunch to a hungry classmate.

What it reveals: Compassion, empathy, generosity.

2. Dialogue (what the character says)

The way a character speaks, tone, word choice, and honesty reveal personality.

Indirect characterization example:

A character constantly interrupts others and dismisses opinions.

What it reveals: Arrogance or insecurity.

3. Thoughts and inner monologue

A character’s private thoughts expose fears, desires, and values.

Example:

A character smiles confidently in public but internally doubts every decision.

What it reveals: Inner conflict, low self-esteem, or pressure to appear strong.

4. Reactions of other characters

How others respond to a character also shapes our understanding.

Example:

If everyone lowers their voice when a character enters the room, the character likely holds authority or inspires fear.

5. Appearance and environment

Clothing, habits, and surroundings offer subtle clues.

Example:

A character with neatly organized books, color-coded notes, and punctual habits suggests discipline or control.

Indirect characterization examples

One of the best ways to understand indirect characterization is to see how famous characters are revealed through their actions, choices, and behavior rather than direct characterization. The following examples show how powerful “show, don’t tell” storytelling can be.

1. Sherlock Holmes

Arthur Conan Doyle never repeatedly tells readers that Sherlock Holmes is a genius. Instead, Holmes’s intelligence is revealed through what he notices and how he reasons.

Holmes observes tiny details; others overlook a client’s muddy shoes, a worn sleeve, a nervous gesture, and logically connect them to accurate conclusions. Readers infer his brilliance by watching him solve complex cases step by step, often shocking both the characters around him and the audience.

Indirect traits revealed:

- High intelligence

- Sharp observation skills

- Logical thinking

- Emotional detachment

Holmes’s character works so well because readers experience his intelligence rather than being told about it.

2. Katniss Everdeen (The Hunger Games)

Suzanne Collins rarely describes Katniss as “brave” in direct terms. Instead, Katniss’s courage is revealed through her decisions under pressure.

She volunteers to take her sister’s place in the Hunger Games, a choice that could cost her life. Throughout the story, she repeatedly risks punishment or death to protect others, defy authority, or stay true to her moral code. Even her moments of fear strengthen the characterization, because she acts despite being afraid.

Indirect traits revealed:

- Courage

- Selflessness

- Survival instinct

- Moral strength

By watching Katniss act, readers understand her bravery as something earned, not labeled.

3. Jay Gatsby (The Great Gatsby)

Scott Fitzgerald does not directly tell readers that Gatsby is lonely or emotionally unfulfilled. Instead, Gatsby’s inner emptiness is revealed through contrast and absence.

He throws extravagant parties filled with people, yet rarely participates in them. His wealth is enormous, but his happiness depends on a single unreachable dream: Daisy. Even in crowded spaces, Gatsby remains distant and quiet, suggesting that money cannot replace genuine connection.

Indirect traits revealed:

- Loneliness

- Obsession

- Emotional vulnerability

- Idealism

Gatsby’s silence and isolation speak louder than any explicit description ever could.

Indirect characterization requires readers to:

- Observe details carefully

- Interpret clues instead of expecting explanations

- Think critically about behavior and motivation

- Actively participate in understanding the story

This makes reading more engaging but also more demanding.

How should a reader analyze indirect characterization?

Indirect characterization asks readers to become active observers, not passive readers. Instead of being told who a character is, you’re invited to figure it out on your own. Here’s how to do that naturally:

1. Watch for patterns

One single action doesn’t define a character, but repeated behavior does. If a character repeatedly avoids responsibility, interrupts others, or puts themselves in danger for someone else, those patterns point to real personality traits.

Ask yourself, “Does this character keep doing this?” If the answer is yes, that behavior is intentional and meaningful.

2. Pay attention to contradictions between words and actions

Characters don’t always say what they mean, and that’s where indirect characterization shines.

A character might claim they don’t care, yet feel hurt when ignored. Or they may call themselves brave but hesitate when action is required. These gaps reveal inner conflict, fear, insecurity, or denial.

Highlight moments where actions and dialogue don’t match. Then ask, “Which one feels more honest?” (It’s usually the action.)

3. Notice how other characters respond

Sometimes, the clearest description of a character comes from how others treat them.

If people trust a character with secrets, they’re likely reliable. If everyone walks on eggshells around someone, that person may be intimidating or unpredictable.

Watch reactions like silence, respect, fear, admiration, or avoidance. These responses often reflect a character’s reputation more accurately than self-description.

4. Ask “What does this reveal?” after key moments

Every meaningful action, choice, or line of dialogue exists for a reason.

When something stands out, pause and ask: “What does this moment tell me about who this character really is?”

Even small details like how a character treats a waiter or reacts to failure can reveal values and priorities. Turn scenes into clues. If a detail feels important, it probably is.

5. Trust yourself as a reader

There is rarely only one “correct” interpretation. The difference between direct and indirect characterization is that indirect characterization is designed to let readers draw conclusions based on evidence. If your interpretation is supported by actions and patterns in the text, you’re analyzing it correctly.

If you can explain why you think a character is kind, selfish, brave, or conflicted using examples, you’ve understood the characterization.

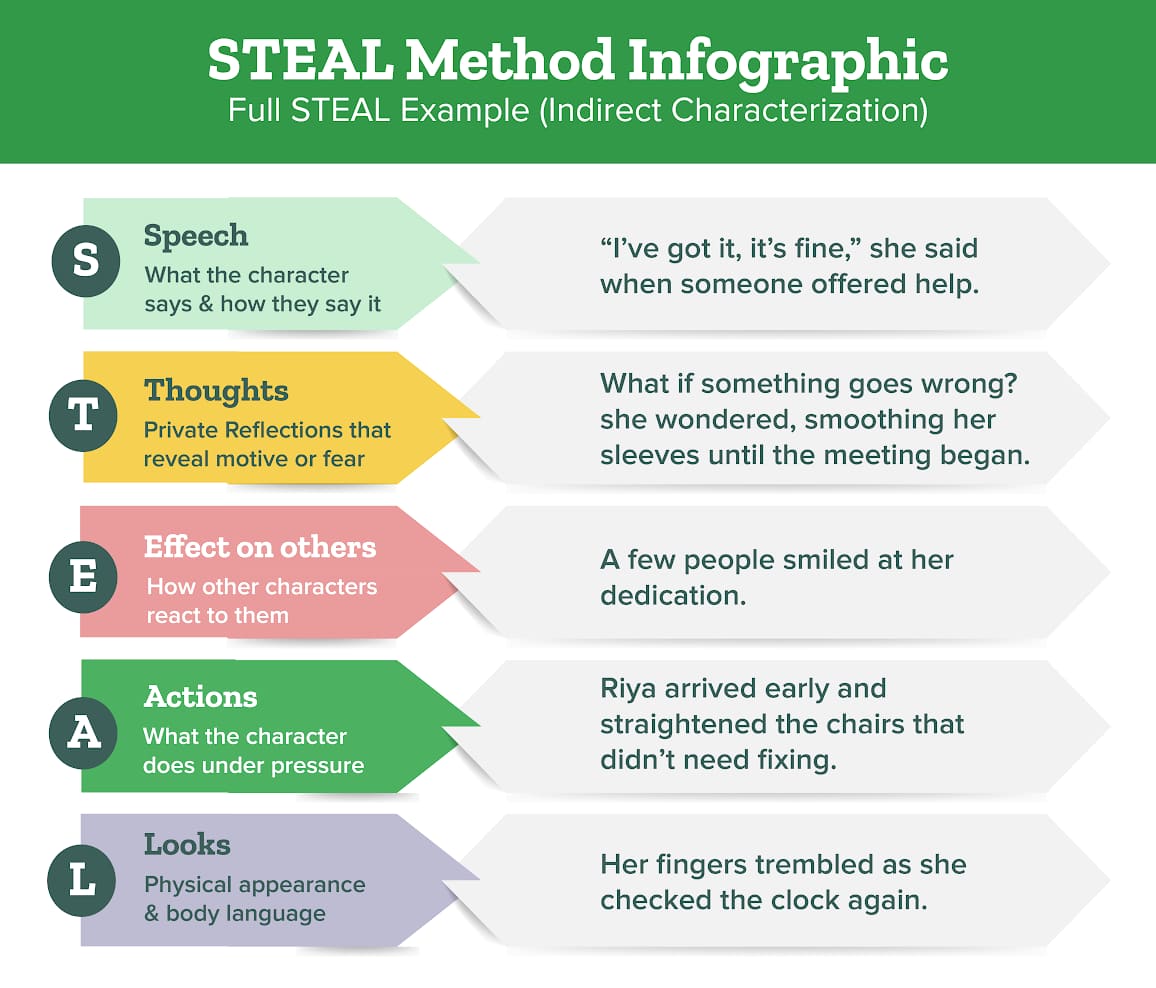

STEAL Method

Writers can use the STEAL method to easily decipher or depict indirect characterization in writing.

For example:

Riya arrived early and straightened the chairs that didn’t need fixing. “It’s fine, I’ve got it,” she said when someone offered help, though her fingers trembled as she checked the clock again. A few people smiled at her dedication, while she silently replayed every possible mistake in her head, smoothing her sleeves until the meeting began.

Practical writing tips for using indirect characterization

1. Replace trait words with specific actions

Instead of telling readers a character’s trait (kind, rude, brave, selfish), show one small action that proves it. Traits are abstract. Actions are concrete.

Telling: She was generous.

Showing: She split her lunch in half and pushed the bigger piece toward him.

The reader understands generosity without the word being used.

How Writers Can Do This

- Write the trait you want (e.g., brave).

- Ask: “What would a brave person DO in this situation?”

- Write that action instead of the adjective.

Trait-to-Action List

Keep a simple list like this:

- Nervous → fidgets, checks phone, avoids eye contact

- Confident → relaxed posture, steady voice

- Angry → clenched jaw, short replies

Use it while drafting scenes.

2. Let dialogue reflect personality, not exposition

Dialogue should sound like something a real person would say, not a personality description. Characters shouldn’t explain themselves to the reader.

Exposition Dialogue: “I am a very independent person who doesn’t trust others.”

Character-Revealing Dialogue: “I’ll handle it myself. I always do.”

The second line sounds natural and reveals independence.

How Writers Can Do This

1. Give each character a speech habit:

- Short sentences = blunt or guarded

- Rambling = anxious or enthusiastic

- Formal language = controlled or distant

Let characters avoid saying things directly.

3. Show emotions through body language

Emotions become real when they appear in the body, not as labels.

Telling: He was angry.

Showing: He set the glass down harder than necessary and didn’t look at her.

Readers feel the anger without being told.

How Writers Can Do This

Focus on small, involuntary movements:

- Hands tightening

- Breathing changing

- Avoiding or holding eye contact

Body Language Cheat Sheet

- Fear → shallow breathing, stepping back

- Guilt → avoiding eyes, overexplaining

- Excitement → fast speech, restless movement

Use 1–2 body cues per scene (not all at once).

4. Trust the reader

Once you’ve shown something clearly, stop explaining it. Readers enjoy figuring things out—it makes the story more immersive.

Over-Explaining: She laughed, but she wasn’t really happy. She was pretending because she felt lonely.

Trusting the Reader: She laughed too loudly, then fell silent when no one noticed.

The emotion is clear without explanation.

How Writers Can Do This

1. Remove sentences that start with:

- This shows that…

- She felt…

2. Ask: “Is the action already doing the work?”

Delete-and-Test Method

Delete the explanatory sentence. If the meaning still comes through, keep it deleted.

5. Reveal traits gradually, not all at once

Real people don’t reveal everything immediately, nor should characters. Let traits emerge over time through repeated behavior.

Too Fast: In one scene, kind, brave, funny, loyal, and insecure.

Gradual Reveal

- Scene 1: Character hesitates

- Scene 3: Character avoids confrontation

- Scene 6: Character finally speaks up

Now the growth feels earned.

How Writers Can Do This

- Choose 2–3 core traits per character.

- Show each trait multiple times in different situations.

- Allow contradictions; people are complex.

Character Trait Tracker

Create a simple note:

1. Trait: Insecurity

- Scene 2: avoids eye contact

- Scene 5: over-prepares

- Scene 9: self-doubt in thoughts

This keeps characterization consistent and realistic.

Indirect characterization brings stories to life by allowing readers to actively uncover who a character truly is. Rather than relying on direct descriptions, writers use behavior, speech, and reactions to show personality in a natural and engaging way.

This technique not only strengthens storytelling but also encourages readers to think critically and emotionally connect with characters. When used skillfully, indirect characterization transforms simple narratives into immersive, unforgettable experiences, proving that sometimes, what’s shown is far more powerful than what’s told.

If you’ve used indirect characterization in your story and want to make sure that it is correct, you can take the help of expert book editing services like PaperTrue! They will correct all the errors and help you in your book publishing journey as well.

Keep on reading for more:

Frequently Asked Questions